“Home of Mrs. George Madden Martin”

(Author of Emmy Lou)

This clapboard Victorian gingerbread may once have been the home or summer home of George Madden Martin, the pen name of early 20th century authoress Mrs. Attwood R. Martin. Relative to other Pewee Valley landmarks, the location is correct and it is the only candidate of the appropriate age in the area; however, the Oldham County Historical Society is conducting a title search to determine its ownership at the time the Lloydsboro Valley map was drawn.

While the house did not play a role in the “Little Colonel” stories as far as we know, there was a real-life relationship between George Madden Martin and Annie Fellows Johnston. Both were members of the Authors Club formed in the 1890s, according to a footnote to a “Time” magazine article about the Little Colonel movie published in the March 11, 1935 issue:

“In the 1880s three young married women in Louisville formed an informal literary club, began three novels which they read to each other at meetings. The young women were Alice Hegan Rice, “George Madden Martin” (Mrs. Atwood R. Martin), and Annie Fellows Johnston.

[Below: Alice Hegan Rice]

Annie Fellows Johnston wrote about her experiences with the Authors Club in her autobiography, “The Land of the Little Colonel,” published in 1929:

Annie Fellows Johnston wrote about her experiences with the Authors Club in her autobiography, “The Land of the Little Colonel,” published in 1929:

That summer our little Author’s Club came into being. Evelyn Snead Barnett proposed it. She was spending the summer at the Inn in Pewee Valley. George Madden Martin and Eva Madden were living in the valley then, and the four of us used to meet with Miss Allison to discuss methods of writing. It was always a little club, never more than seven or eight, but later on it numbered the author of “Mrs. Wiggs of the Cabbage Patch” and the “Lady of the Decoration” among its members; also Abby McGuire Roach, Mary F. Leonard, Margaret Vandercook, Margaret Steele Anderson, and Ellen Semple. Each of them has one book to her credit and some of them many more. Later, Eleanor Mercein Kelly joined us.

After that summer we met in Louisville once a week for over twenty years. At the meetings the members took turns reading a manuscript, which was duly criticized. In all that time I never knew of one of the members getting her feelings hurt, for we took the criticisms gladly and profited by them.

At one time this was given to the Club to work out: “A well bred young lady in a barber shop at midnight. How did she get there and how did she get out?” Each one told a different tale. The Black Cat magazine took them all and devoted one entire number to the collection of tales.

We always had some sort of frolic every year. The tie that bound us was a very strong one and our friendship was deeply rooted. The memory of it is one of my most cherished possessions.

Of the three young women, Annie Fellows Johnston was first to find fame and fortune through her pen, when “The Little Colonel ” was published in 1895. Both George Madden Martin and Alice Hegan Rice published their best-selling children’s books in 1902: Madden with “Emmy Lou: Her Book and Heart” and Rice with “Mrs. Wiggs of the Cabbage Patch .”

According to “History of Old Louisville: The People ” by Margaret M. Bridwell, “In the early 1900’s the members of the Authors Club published more than seventy volumes.”

Undoubtedly, Authors Club members discussed both the joys and tribulations of commercial success. Answering fan mail and requests for autographs could certainly be counted among the tribulations. In this excerpt from Chapter IV, “The Shadow Club ” from “The Little Colonel at Boarding School,” Annie Fellows Johnston describes the tremendous time and expense involved in answering all those letters:

…the principal found twenty-three letters in the mail-bag one morning, all addressed to a well-known writer of juvenile stories, whose books were the most popular in the school. An investigation proved that because one girl had received his autograph, twenty- three had followed her example in requesting it, and not one of them had enclosed a stamp; nor had it occurred to them that an author’s time is too valuable to spend in answering questions, merely to satisfy the idle curiosity of his readers.

“One stamp is of little value,” said the principal, “but multiply it by the hundreds he would have to use in a year in answering the letters of thoughtless strangers, who have no claim on him in any way.” Twenty-three girls filed out into the hall after the principal’s little talk that followed, and slipped their letters from the mail-bag. Ten of them threw theirs into the waste-basket. The others, who had asked no questions and were more desirous of obtaining their favourite author’s autograph, opened theirs to enclose an envelope, stamped and addressed; but few more letters of the kind went out from Lloydsboro Seminary after that.

Was Johnston talking about herself or, by referring to the author in question as male, was she making a veiled reference to her friend, who wrote under the pen name George Madden Martin?

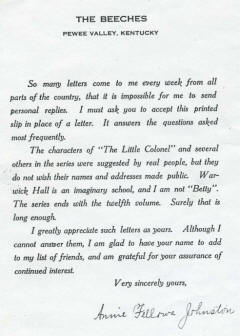

form letter young readers would often receive from Annie Fellows Johnston.

(click on image to enlarge)

**********************

Biographical Information about George Madden Martin

(May 3, 1866-November 30, 1946)

George Madden Martin was born in Louisville in 1866 to Frank and Anne Louise (McKenzie) Madden. Both she and her sister, Eva, attended Louisville public schools, although Mrs. Martin was forced to finish her education at home due to health problems.

She published her first book, “The Angel of the Tenement,” in 1897, but it met with little commercial success. In later years, she seldom listed it among her published works.

Her first and greatest literary achievement was “Emmy Lou: Her Book and Her Heart,” published in 1902. The book actually began as series of stories that appeared serially in “McClure’s Magazine” from 1900 to 1901:

(From her obituary in the “Courier-Journal,” December 1, 1946):

“…Begun as a short story, ‘Emmy Lou” came to the attention of Lincoln Steffens, then editor of McClure’s magazine. He visited Mrs. Martin at her home, then in Anchorage, and arranged for publication of all her future work. In the next 20 years, she wrote more than half a dozen novels on the activities of Emmy Lou…

A “Literary History of Kentucky” by William S. Ward, published by the University of Tennessee Press in 1988, describes the book’s commercial success and the reasons why it appealed to such a large audience:

(page 124)

“…The stories had been widely read in serial form, of course, but as a volume they were an even greater success and went into frequent reprinting and eventually sold well above two hundred thousand copies. The reason for this popularity was in part Martin’s skill as an author, but it was also due to the fresh and different subject matter. She dealt with the problems of a charming, born-to-be-loved little girl who is slow to learn in school but is always faithful and always tries. By implication, Mrs. Martin is saying that current methods of teaching are not designed for such children, with the result that their road is difficult and life frustrating. Since counterparts to Emmy Lou were to be found in all schools and many homes, the book appealed to a wide audience and remained a steady seller for forty years or more, was never out of print, and is credited with motivating change in teaching methods…”

Some of Mrs. Martin’s other books included: “Abbie Ann,” published in 1907; “Children in the Mist,” published in 1920; and “Made in America,” published in 1935. For Kentucky’s sesquicentennial, she penned the story of Jane Todd Crawford – the patient with the ovarian tumor who brought Danville’s Dr. Ephraim McDowell fame as a pioneer in abdominal surgery. It was published in “The Kentucky Medical Journal.” None of her subsequent works, however, enjoyed the popular acclaim of “Emmy Lou.”

Mrs. Martin was not only author. She was also a champion of social reform, according to an Op-Ed piece titled “The Mother of ‘Emmy Lou’ A Distinguished Citizen” that appeared in the December 2, 1946 edition of the “Courier-Journal”:

Mrs. Martin contributed much more to her community than the reflected glory of her success as a novelist and contributor to the leading national magazines. She took her obligations as a citizen seriously…She was in politics – a member of the Democratic State Committee in the League of Nations campaign of 1920. She later was a Kentucky leader of the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform…

…But perhaps she will better be remembered for her intelligent and long-continued work in the promotion of better racial relations. She was a charter member of the Commission on Interracial Co-operation and served as head of the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching. The latter organization attached the pretext that lynching survived for ‘the protection of Southern womanhood.’ It showed that, where lynching was concerned, all sorts of base reasons were hiding behind the skirts of Southern womanhood.

Mrs. Martin also had the unique privilege of becoming the first woman ever to be made a Kentucky Colonel.

George Madden Martin’s Anchorage home. Known as “Anchorage Place” or the “Old Goslee Place,” it was originally built by riverboat captain James W. Goslee and his wife, Catherine Ramsey White Goslee in 1868 for $12,476. The Martins owned the property from 1906 until 1913, according to “The Village of Anchorage” by Samuel W. Thomas, published by the Anchorage Civic Club, 2004. Today, it is considered one of Anchorage’s most historic residences. Photo from the Kentucky Digital Library’s Herald-Post photographs collection, digital ID klgsc:klgsculrsc021:94.18.0259

After her husband, Attwood R. Martin, died in July 1944, she moved from her Anchorage home to live with friends at 1304 Eastern Parkway. She died there on November 30, 1946, leaving $8,000 in cash to her sister Eva, her sole survivor. She is buried in Cave Hill Cemetery, Section O, Lot 275, grave 9.

Just as Annie Fellows Johnston did not live long enough to see “The Little Colonel” reach the silver screen, neither did Mrs. Martin live to see Emmy Lou, when it appeared in 1960 as an episode of the popular television program, Shirley Temple’s Storybook, with Bernadette Withers starring as the title character.

Photos of George Madden Martin from

The Kentucky Digital Library

Herald-Post collection

|

|

|

|

|

| no date | 1923 | 1927 | 1930 | no date |

page by Donna Russell