“The Beeches: The Johnston Years and Beyond”

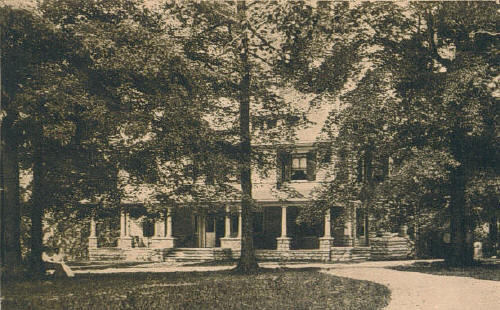

Final home of Annie Fellows Johnston and her stepdaughter, Mary Gardener Johnston

Go to The Beeches: The Lawton Years

A Beeches Postcard signed by Mary G. Johnston from the Samuel Culbertson Mansion’s collection

After her stepson, John, died from tuberculosis at the family’s Penacres home in Texas, Annie Fellows Johnston returned to Pewee Valley, where the “Little Colonel” stories began. In 1911, she purchased The Beeches from long-time friend and confidante, Mrs. Lawton, and lived there with her last remaining stepchild, Mary Gardener Johnston, for the rest of her life. Their move to The Beeches was noted in the April 9, 1911 edition of “The Galveston Daily News” State Society column under items from Boerne (the “little town of Bauer in Mary Ware in Texas):

Mrs. Annie Fellows Johnston and her daughter left for their new home in Pewee Valley, Kentucky, Friday (April 7, 1911)

The author’s reason for purchasing the spacious home, said her daughter in a 1963 interview, was the garden, which also frequently attracted the eye – and camera — of the two women’s mutual friend, photographer Kate Matthews.

According to Katie Smith’s 1974 “The Land of the Little Colonel,” after returning to Pewee Valley, “…Mrs. Johnson continued to write, usually from 9am until noon. After lunch and a rest, Mrs. Johnston and Miss Mary would often take walks along our shaded avenues…” Miss Mary would keep quiet in the mornings, while her stepmother worked in her upstairs study, located on the backside of the house overlooking the garden. A description of her study is included in a July 19, 1963 “Courier-Journal” story called “Reminiscences of ‘Little Colonel’” written by Susan Clarke:

… Miss Mary showed the way to the study and pointed out the typewriter Annie Fellows Johnston used. A tall clerk’s desk, painted white, stood next to the window. When her mother tired of sitting, she would transfer her papers and continue to work there, standing up.

Above the desk hangs a large prism. “Mother used to like to look at things through it,” Miss Mary said. It was given to the author after her book, “Georgina of the Rainbows” was published.

Another gallery of photographs lined a wall of the study. Miss Mary pointed out some of the early members of the Louisville Writer’s Club. Annie Fellows was one of the first….

Evansville, Indiana reporter Jeannette Covert Nolan supplied additional details about the room where Annie practiced her craft in a c.1940s article called “Return from Kentucky.” It was, she wrote:

“…an airy room with white woodwork and furnishings, frilled white curtains at the windows and Chinese matting on the floor. The door still bears the metal placard lettered ‘Headquarters’ which Mrs. Johnston hung there and the decorative knocker hung there by the Little Colonel. Mrs. Johnston liked crystals and you will see several on her desk and suspended above it. Beside one window is the sturdy ‘standing desk’ which she designed – because, as Miss Mary says, “she got so weary of sitting down to her writing.”

The walls are lined with framed photographs. I noticed among them, prominently displayed, pictures of two Hoosiers who were Mrs. Johnston’s contemporaries, James Whitcomb Riley and Cale Young Rice. There is also a group of photographs of members of the “Author’s Club” which Mrs. Johnston founded and which was to develop such talents as that of Alice Hegan Rice, George Madden Martin, Frances MacCauley and Eleanor Mercein Kelly. Scattered liberally in this room and over the whole house are photographs of the Little Colonel, her friends and companions.

The Beech’s second-floor study where Annie Fellows Johnston did her writing

Photo from “Land of the Little Colonel,” published by Katie Smith in 1974

It was in this second floor writing room that Annie Fellows Johnston penned Mary Ware’s Promised Land (1912), Miss Santa Claus of the Pullman (1913), Georgina of the Rainbows (1916), Georgina’s Service Stars (1918), The Little Man in Motley (1918), The Story of the Red Cross (1918), It Was the Road to Jericho (1919), The Road of the Loving Heart (1922) and her autobiography, The Land of the Little Colonel (1929).

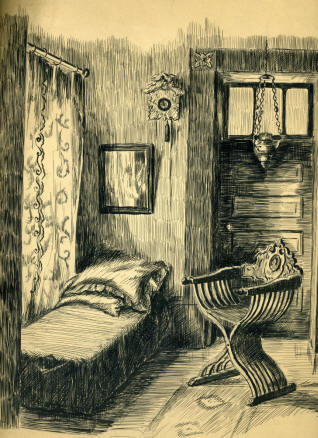

Mary Johnston, who illustrated some of the “Little Colonel” books, had an art studio in The Beech’s third floor attic. A sketch of the studio by the artist, herself, is shown below. The attic, recalls Suzanne Schimpeler, had a wonderful smell, probably due to the linseed oil in her paints.

Miss Mary’s sketch of her third-floor art studio,

from the private collection of Suzanne Schimpeler

During the years Annie Fellows Johnston was alive and for years after her death, The Beeches was a Mecca for “Little Colonel” fans, who traveled from points far and wide to see it. Both Annie and Mary graciously welcomed many of these unexpected strangers inside and would sign photos, post cards and books for them as souvenirs. A May 15, 1937 “Louisville Times” story written by Harry Bloom told how one of those pilgrims took it upon himself to place a sign at the property’s entrance to make it easier for visitors to find:

ABOUT A YEAR AGO, Andrew Sandegren, Chicago architect, while touring Kentucky with his family, wanted to see the home of the late Mrs. Annie Fellows Johnston, Pewee Valley, creator of the Little Colonel stories. There were no signs to guide him and he had to ask so many questions to find “The Beeches,” that he decided something ought to be done about it. He did it himself. With the permission of Mrs. Johnston’s daughter, Miss Mary Johnston, he erected a neatly-lettered sign at the entrance: “The Beeches – Annie Fellows Johnston” to guide all lovers of the Little Colonel stories to their shrine.

This year brought a sequel. Not very well acquainted with this part of the country, Mr. Sandegren didn’t know whether “The Beeches” was in the floor territory. Last week when he, Mrs. Sandegren and her mother came to the Derby he decided to see for himself whether the sign had suffered flood damage, and if so to replace it.

They motored out from Louisville and were happy to learn that the sign was intact. The sign has saved Pewee Valley neighbors a lot of doorbell ringing by inquiring tourists. The Little Colonel’s hold on young and old alike grows with the passing years and the stream of visitors increases constantly. Last Sunday fifteen motor parties called within two hours and the record for a single day is ninety-eight. All are warmly welcomed by Miss Johnston.

Though many also requested directions to The Locust, Miss Mary usually discouraged them:

(“Pewee Valley” by Hewitt Taylor, August 29, 1936 Louisville Herald Post)

Most of all the visitors ask the way to The Locusts, but Miss Johnston advises them to pretend they have seen the picturesque place. Locust Lodge is not actually the home described in the book and is disappointing to most.

The stately drive, arched by locust trees, is the same, however, and one expects to see the old Colonel peering down the avenue at the strangers looking in the gate.

According to Annie Fellows Johnston’s obituary from the October 5, 1931 “New York Times,” The Beeches not only attracted “Little Colonel” fans. Soldiers from Ft. Knox also visited by the score after “Georgina’s Service Stars,” was published in 1918

After her stepmother’s death in 1931, Mary Johnston kept The Beeches much the same as it was while Annie Fellows Johnston was alive – a task that would have proved impossible without the assistance of Walker Hardin, Jr., son of the “Walker” who served as the model for the Old Colonel’s valet in the stories:

(From “Reminiscences of ‘Little Colonel’” by Susan Clark, “Courier-Journal,” July 19, 1963)

Miss Mary, who manages “The Beeches” by herself is able to keep the authentic loveliness of the house and grounds with the help of Walker (Hardin), who comes twice a week. “I don’t know how I would find things without him,” smiles the sprightly Miss Johnston. “I lost a checkbook the other day and was looking all over for it. Walker found it under a cushion.”

From the Courier-Journal Magazine, June 22, 1952

That Mary kept her stepmother’s effects intact later proved to be a blessing to Berea College, which secured the original manuscript of her unfinished novel, “A Mountain Mailbag,” twenty-three years after the author’s death. Left in a briefcase since Annie Fellows Johnston set it aside when she first became ill with the cancer that later claimed her life, “A Mountain Mailbag” told the story of the struggles of young mountain people who wanted an education. The mountain schools of Kentucky had long been a cause dear to her heart and she first wrote about them in “The Little Colonel at Boarding School,” published in 1904. A July 25, 1954 Courier-Journal Magazine article by Adele Brandeis recounts the tale of how the manuscript eventually found its way to Berea College:

This year Dr. Elizabeth Peck of the history department, who has been at Berea “man and boy” since 1912, was made college historian. She immediately took over (the papers of Dr. William J. Hutchins, who was president of the college in 1920).

To her great excitement, being a “Little Colonel” fan, she found two letters from Annie Fellows Johnston, dated 1919 and 1920, in which the author wrote:

“I am very busy with a work which I hope will be of profit to Berea, indirectly. It is a book about the mountain people themselves, putting their various problems in a story which I hope will have as wide an influence as my other books seem to have exerted. It is to be called “A Mountain Mailbag”…D. Appleton and Company, who will publish the book, are quite enthusiastic.”

“How strange,” thought Dr. Peck, “that I have never read that book.” There was no copy in the college library. And when she wrote the Louisville Free Public Library staff, they reported that not only was the book not in the library, but they could find no record of its publication. Dr. Peck was non-plussed – but not for long.

She knew Mrs. Johnston had lived with her daughter, Miss Mary Johnston at Pewee Valley, so she wrote to ask her: “Where is that book?”

The letter, when it arrived at Miss Johnston’s home, “The Beeches,” created great interest. For Mrs. Johnston had had the original manuscript ever since the beginning of the author’s long illness in 1920. It had rested there in Pewee Valley all this time in its original briefcase.

Miss Johnston immediately sent the first two chapters to Dr. Peck and asked her to go over them, explaining that the briefcase contained parts of 16 chapters and a heading for a 17th –_ some quite complete, some fragmentary, some only in summary. They were in typescript with notes in Annie Fellows Johnston’s handwriting.

Berea wrote back that they wished they might own the manuscript, but could not afford to buy it, and did not know whether in its incomplete state anyone would publish it. But they asked if they might have it on loan for display…

Miss Mary Johnston said she would be delighted to give the manuscript to Berea. She has been wondering for years what she ought to do with it to make it accessible for she that interest in Mrs. Johnston’s work had never waned….

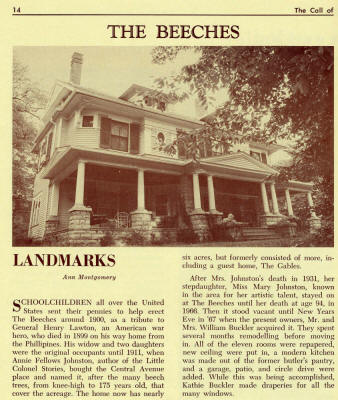

A “Call of the Pewee” article from a special bicentennial issue provides information about renovations made to the home’s interior after Mary Johnston’s death in 1966.

Click pages to enlarge

Use your browser’s back arrow to return

Thanks to Sue Berry and Alex Luken for sending us newspaper clippings from the Louisville Free Public Library’s York Street branch and the Kentucky Historical Society’s library in Frankfort, Ky. that are quoted on this page. Also special thanks to Suzanne Schimpeler for sharing her sketch of Mary Johnston’s studio and to Margie Fletcher Thompson for the color photo of The Beeches from 1952