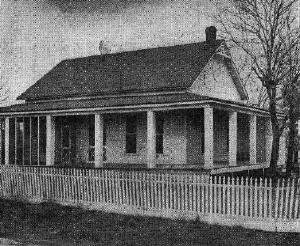

Penacres: The Johnstons’ Home in Boerne, Texas

And the Model for the Cottage Rented by the Wares

in “Mary Ware In Texas”

We went back to Comfort for a while and then moved to Boerne where I bought a place that we called Penacres.

–Annie Fellows Johnston, in Land of the Little Colonel, Chapter 8

“In this home, Mrs. Johnston lived with her son, John E., who died in Boerne in 1910, and her daughter, who kept house while her mother wrote books,” according to a 1949 article from the “Evening News.” The house was located at 609 E. Theissen Street. Newspaper clipping courtesy of the Boerne Area Historical Society.

In 1906, Anne Fellows Johnston reached a milestone in her life when she purchased land and a house in Boerne, Texas.

Buying the little farm she named “Penacres” – because she earned the money with her pen — was a symbol of how far the novelist had come since she first attempted to support herself and her three stepchildren with her writing. Widowed in 1892 after a few short years of marriage and with very little money to her name, Annie managed to hang on to the Johnston homestead in Evansville for five years after her husband’s death, but, according to her autobiography:

“In September, 1897, we came to a turn in the road where we could see only one step ahead at a time. Rena joined Mary in Pewee Valley; I sold or stored our household goods and took John up to Highland Park to put him in the military school there.”

It was eight years before she purchased another home for her stepchildren, and by 1906, when she bought Penacres, only two of her stepchildren, John and Mary, were living. Her third stepchild, Rena, died unexpectedly of appendicitis in 1899 (see “The Tremonts”) while living with her aunt, uncle and cousin at Delacoosha, in Pewee Valley.

Why did it take Annie so long to buy another home? Money, of course, was an issue, and the Johnstons’ lack of it was reflected in many of her novels, especially in the trials and tribulations faced by the Ware family. The difficulties of those who, unlike “The LittleColonel” Lloyd Sherman , had to work hard for a living were the underlying theme in The Little Colonel in Arizona, Mary Ware: The Little Colonel’s Chum and Mary Ware in Texas. All three books are rife with examples of small economies and resourceful enterprises the Wares employed to keep the proverbial wolf from the door.

The other issue that stood in the way of a permanent home was John’s consumption. Annie and John, joined from time to time by Mary, lived a Bedouin’s existence for many years in search of TB-friendly climes. New York, California and Arizona were some of the places they lived before heading to the Texas Hill Country. Even after arriving in Texas, they boarded in Comfort and San Antonio for several years before buying a home in Boerne.

So what actually led Annie to purchase Penacres?

If Mary Ware’s private bedtime musings in Chapter 2 of Mary Ware in Texas accurately reflect the author’s state of mind, Annie and her children had grown tired of wandering and were ready to put down roots:

“How lovely it must be to have an ancestral roof-tree,” thought Mary that night, as she tossed, restlessly, kept awake by the noises of the big hotel. “I can’t think of anything more heavenly than to always live in the house where you were born, and your fathers and grandfathers before you, as the Lloyds do at The Locusts http://www.littlecolonel.com/theLocust.htm. It must be so delightful to feel that you’ve got an attic full of heirlooms and that everything about the place is connected with some old family tradition, and to know that you can take root there, and not have to go wandering around from pillar to post as we Wares have always had to do. I wonder if Lloyd Sherman http://www.littlecolonel.com/Little_Colonel.htm knows how much she has to be thankful for!”

We also know that by the time Annie purchased Penacres, John’s condition had grown much worse. As Annie noted in her autobiography:

“That fall I joined John and Mary in San Antonio, and we kept house there till the following June. John had grown so much better that he was travelling for a wholesale paper house, but was taken violently ill in May and we had to take him to the hill country. We went back to Comfort for a while (where there was a ranch for invalid borders) and then moved to Boerne where I bought a place that we called Penacres.”

Once she resigned herself to the fact that John would never recover, Annie may have decided her family deserved more settled surroundings than invalid ranches and tent communities could provide. By making a permanent home in the Texas Hill Country, John would still benefit from the clean, dry air and the family could stay together in relative comfort.

Renting may not have been an option, since John’s illness had reached the stage where he was frequently seized by paroxysms of coughing. Chapter 2 of Mary Ware in Texas describes the discrimination “lungers” and their families faced in San Antonio when they tried to rent houses or take rooms in boardinghouses:

…In her search for rooms a new difficulty faced her. Invariably one of the first questions asked her was, “Anyone sick in your family?”

“Yes, my brother,” she would say. “He has rheumatism. That is why we are particular about getting a sunny south room for him.”

“Well, we can’t take sick people,” would be the positive answer, and she would turn away with an ache in her throat and a dull wonder why Jack’s rheumatism could make him objectionable in the slightest degree as a tenant. The morning was nearly gone before she found the reason. She was shown into a dingy parlor by a child of the family, and asked to wait a few moments. Its mother had gone around the corner to the bakery, but would be right back.

There were two others already waiting when Mary entered the room, a stout, middle-aged woman and a delicate-looking girl. The woman looked up with a nod as Mary took a chair near the stove and spread out her damp skirts to dry.

“I reckon you’re on the same errand as us,” said the woman, “but it’s first come, first served, and we’re ahead of you.”

“Yes,” answered Mary, distantly polite, and wondering at the aggressive tone. When the child left the room the woman rose and shut the door behind it, and then came back to Mary, lowering her voice confidentially.

“It’s just this way. We’re getting desperate. We came down here for my daughter’s health — the doctor sent us, and we’ve gone all over town trying to get some kind of roof over our heads. We can’t get in anywhere because Maudie has lung trouble. People have been coming down here for forty years to get cured of it, and folks were glad enough to rent ’em rooms and take their money, till all this talk was stirred up in the papers about lung trouble being a great white plague, and catching, and all that. Now you can’t get in anywhere at a price that poor folks can pay. I’ve come to the end of my rope. The landlady at the boardinghouse where we’ve been stopping, told me this morning that she couldn’t keep us another day, because the boarders complained when they found what ailed Maudie. I was a fool to tell ’em, for she doesn’t cough much. It’s only in the first stages. After this I’m just going to say that I came down here to look for work, and goodness knows, that’s the truth! What I want to ask of you is that you won’t stand in the way of our getting in here by offering more rent or anything like that.”

“Certainly not,” Mary answered, drawing back a little, almost intimidated by the fierceness which desperation gave to the other’s manner.

The landlady bustled in at that moment, and as she threw the rooms open for inspection, she asked the question that Mary had heard so often that morning, —“Any sick in your family?”

“No,” answered the woman, glibly. I’m down in the city looking for work. I do plain sewing, and if you know of any likely customers I’d be glad if you’d mention me.”

The landlady glanced shrewdly at Maudie, who kept in the background.

“She does embroidery,” explained her mother. “Needle-work makes her a little pale and peaked, sitting over it so long. I ain’t going to let her do so much after I once get a good start.”

“Well, a person in my place can’t be too careful,” complained the landlady. “We get taken in so often letting our rooms to strangers. They have all sorts of names for lung trouble nowadays, malaria and a weak heart and such things. The couple I had in here last said it was just indigestion and shortness of breath, but she died all the same six weeks later, in this very room, and he had to acknowledge it was her lungs all the time, and he knew it.”

Though Boerne’s climate could prolong John’s life, the town itself left much to be desired in terms of amenities. To start with, it was a quiet, close-knit German community, which did not welcome outsiders, as Mrs. Barnaby noted in Chapter 3:

They don’t want any disturbing, aggressive Americans in their midst, so they never call on new-comers, and never return their visits if any of them try to make the advances. They will welcome you to their shops, but not to their homes.

With a population between 800 and 900, Boerne also couldn’t provide the many interesting diversions available in nearby San Antonio, which boasted more than 53,000 residents at the turn of the 20th century –shopping, the public library, historic sites, the Army officers, the music and the exciting hustle and bustle of its streets – all entertainments Mary and Mrs. Ware obviously relished when they first arrived in Texas and were staying at a San Antonio hotel (From Chapter 1 of Mary Ware in Texas):

“This certainly is great! What a world of things we’ve been missing all these years, little mother! I never realized just how much we have missed till I went East last year. Then afterwards the days were so full of work and the new responsibilities that I didn’t have time to think about it much. But I can see now what a dull gray existence you’ve had, for as far back as I can remember there’s only been three backgrounds for you: a little Kansas village, a tent on the edge of the Arizona desert, and a lonely mining camp. How long has it been since you’ve seen a sight like this?”

The scattered violets were all picked up now, but Mary still stood by the table, waiting for her mother’s reply.

“It’s so long ago I’ll have to stop and count up. Let me see. You’re twenty-two and Joyce twenty-three — really it’s almost a quarter of a century since I’ve been in a large city, and seen anything like this in the way of illuminations, with music and crowds. Your father took me to New York the winter after we were married. Before that I’d always had my full share. I’d visited a great deal and travelled with Cousin Kate and her father. And I’m sure that no one could want anything brighter and sweeter and more complete than life as I found it as a girl, in ‘my old Kentucky home.’ As I had so much more than most people the first part of my life I couldn’t complain when I had less afterwards. But I certainly do enjoy this,” she added earnestly, as the orchestra began the haunting air of the Mexican “Swallow Song,” La Golondrina, and the odor of roses stole up from below. The court was filled now with gay little groups of people who had the air of finding life one continual holiday.

When Mary Ware voices her frustrations about spending the winter in Boerne in Chapter 3 of Mary Ware in Texas, was she actually voicing the frustrations of the author and her stepdaughter?

MARY was the only one to whom the change of plans made a vital difference. She had built such lovely dream-castles of their winter in San Antonio that it was hard to see them destroyed at one breath.

“Of course it’s the only thing to do,” she said, in a mournful aside to Norman, “but did you ever dream that there was a dish of rare, delicious fruit set down in front of you, so tempting that you could hardly wait to taste it, and just as you put out your hand it was suddenly snatched away? That’s the way I feel about leaving here. And I’ve dreamed of getting letters, too; big, fat letters, that were somehow going to change my whole life for the better, and then just as I started to read them I always woke up, and so never found out the secret that would make such a change in my fortunes.”

“Maybe it won’t be so bad after all,” encouraged Norman. “Maybe we can have a boat. There’s a creek running through the town and the Barnaby ranch is only seven miles out in the country. We’ll see them often.”

Mary wanted to wail out, “Oh, it isn’t boats, and ranches, and old people I want! It’s girls, and boys, and something doing! Being in the heart of things, as we would be if we could only stay here in this beautiful old city!”

Whatever her true feelings about living in Boerne, Annie did as she always did. She cheerfully made the best of the situation and continued her work. While living at Penacres, she wrote three of the novels in the Little Colonel series: Little Colonel’s Knight Comes Riding (1907), The Little Colonel’s Chum: Mary Ware (1908), and Mary Ware in Texas (1910). Penacres, itself, was incorporated in her stories, when it served as the model for the cottage the Wares rented from Mr. and Mrs. Metz in Mary Ware in Texas.

In the book, the cottage was described as located “on a slight knoll with a wide cotton-field stretching down between it and the little village.” There was a windmill in back, which became a “fine watch-tower,” providing the Wares – and the Johnstons — with a panoramic view of the surrounding countryside and Cibolo Creek. “The kitchen,” Annie wrote, “was located in an ell of the house and the road was visible from its front window.” Across the road stood two blue-roofed cottages.

Page 124 of Images of Boerne describes Penacres as a “two-room house with a hallway” that was “built in 1896 by Charles Schwartz.” Kendall County deed records (Vol. 16; p. 414 and Vol. 18, pp. 348-349) verify that Charles Schwartz did, indeed, own the property at one time and sold it to August Schweppe in 1901.

Additional information Col. Bettie Edmonds of the Boerne Area Historical Preservation Society has gleaned from the Kendall County deed records shows that the property encompassed 3.5 acres and was purchased from George E. and Laura J. Smith on March 5, 1906 by Annie Fellows Johnston for $2,400 cash (Vol. 22; pp 336- 338). Local histories uniformly give the Johnstons’ Boerne residency dates as 1905 to 1911, so the Johnstons may have rented Penacres for several months before purchasing it or lived for awhile at the Phillips House before the property came on the market.

Though the German community was not especially friendly, Annie managed to make friends among the English and Scotch families who owned the outlying ranches. Two of her closest companions, according to a 1949 article that appeared in the “Evening News,” were Camille Johns, wife of Joe Johns, and Alice Massey, who was married to the rector at St. Helena’s Episcopal Church where the Johnstons attended services. Both women and their husbands became characters in Mary Ware in Texas. Alice’s mother, Mrs. Bliss, who kept a summer home in Boerne, became a friend, as well.

Another acquaintance was Georgina Kendall Fellowes, a possible distant relation who grew up at Post Oaks Springs Ranch, and came back from time to time to visit her mother, Mrs. Kendall-Dane.

It also appears that Annie befriended Wilhelmina Phillips and her daughter, Augusta Phillips Graham, who ran Phillips House – the model for Williams House from which the Mallory family was evicted due to Brud’s and Sister’s devilish behavior in Mary Ware in Texas. Wilhelmina and Augusta may have provided Annie with many of the children’s antics recounted in the story. After years at the hotel, the pair had undoubtedly seen more than their fair share of mischievous children! (To learn more about Phillips House and see a photo, visit the Bauer/Boerne page.)

Unlike the homes in Lloydsborough/Pewee Valley, the dwellings in Boerne were far apart. In a 1908 letter Annie noted:

” I have made a number of calls, which necessitates a good deal of driving as the people we visit are mostly out of town a distance of five miles or so. The ranches are so large that Boerne is like the hub of a wheel from which the roads radiate in every direction. We can never make more than one visit in an afternoon, since every one lives at the end of a different road from any of his neighbors.”

Despite his illness, John also managed to find fulfilling employment as a wholesale curio merchant, fashioning and selling popular armadillo baskets and selling wild animals from Mexico and Texas to zoos. Several of his beasts became family pets, including “Joseph, the wolf, who loved watermelon;” “Crazy Liz, the coyote;” and a “darling little wild cat” named Matilda, according to Annie’s autobiography. His friends nicknamed the lot behind his Armadillery workshop at Penacres “Hell’s half-acre” when he began shipping quantities of non-poisonous snakes to feed boa constrictors at zoos.

He also owned a dog, a brown and white setter named Uncle August, which made several appearances in Mary Ware in Texas. In the story, however, Uncle August was the property of the Mallory family. (To see a picture of Uncle August in front of Phillips House, visit John Johnson’s page.)

While living in Boerne, the Johnstons traveled and friends and relatives also came to visit. The following snippets from the “Comfort News” detail some of their comings and goings:

September 21, 1906: Mrs. Annie F. Johnston has returned to her old home in Indiana for a short visit to her mother.

July 26, 1907: Mrs. Annie Fellows Johnston had as her guest at dinner Saturday Mr. J. Mallon Marshall of New York. (editors note: we been unable to learn Mr. Marshall’s relationship with Annie, but would guess that he worked for L.C. Page, her publisher)

December 20, 1907: Mr. and Mrs. Donald Jacob of Kentucky are spending a month with Mrs. Annie Fellows Johnston. (editors note: Mrs. Donald Jacob was Hallie Burge Jacob, Annie’s niece by marriage. It was while staying at Delacoosha, the Burge family home in Pewee Valley, that Annie met Hattie Cochran and her grandfather, Col. George Washington Weissinger, who inspired her to write the very first Little Colonel story. Hallie’s husband was an architect and the couple moved to San Antonio in 1908.)

October 9, 1908: Miss Mary Johnston returned to Boerne last week after of a visit of several months in Kentucky. (editors note: a letter Annie wrote detailed Mary’s travels as follows: Mamie went back to Kentucky in May to escape the heat. She is as much of an invalid now as John — although not from the same cause. She stayed with Hallie (her cousin in Pewee Valley) till July, then went to Providence, R. I. to spend three weeks with Mrs. Bliss. — (General Bliss’s widow, who has her winter home in Boerne and is one of the most charming old ladies I ever knew). Then she went back to Pewee.)

February 5, 1909: Mrs. Annie Fellows Johnston, Miss Mary Johnston and Mr. John E. Johnston went to San Antonio Wednesday to spend a few days.

April 2, 1909: Mrs. Annie Fellows Johnston left this week for Indianapolis, In., where by special invitation she will on April 2nd, address the state convention of school teachers. Mrs. Johnston will spend a month with relatives at Evansville before returning.

April 30: Mrs. Annie Fellows Johnston returned Saturday after a month in Indianapolis.

Life, in short, was as normal as the Johnstons could make it, despite John’s continuing battle with his health. The family had owned Penacres a little less than five years, when John succumbed to tuberculosis on September 26, 1910. Annie and Mary traveled to Evansville, In. for his burial.

Less than six months later, Annie sold the Boerne property to J.W. Lawhon on March 20, 1911 for $3,800 — $1000 cash and the rest to be paid to her as a lien at eight percent interest (Kendall County Deed Records, Vol. 26; pp.372 – 373). A month later, she, Mary and the little wildcat Matilda left for their new home — The Beeches in Pewee Valley, which Annie purchased from her long-time friend Mary Lawton. (To see a picture of Annie holding Matilda on The Beeches’ front porch swing, visit John Johnson’s page.) As Annie noted in her autobiography:

After John’s death it was so lonely at Penacres that we came back to Kentucky to live.

Their move was recorded in the April 9, 1911 edition of “The Galveston Daily News” State Society column under items from Boerne:

Mrs. Annie Fellows Johnston and her daughter left for their new home in Pewee Valley, Kentucky, Friday (April 7, 1911)

In 1949 during Boerne’s centennial year, the local citizenry announced a plan to donate a bronze plaque to honor Penacres, possibly spurred by a visit to the town by Mary Johnston. That plan never came to fruition, and in fact, Annie’s modest little cottage was eventually demolished and replaced with the modern residence shown in the photo below:

Photo courtesy of the Boerne Area Historical Preservation Society

Though The Beeches in Pewee Valley still exists and looks much as it did when the Johnston’s were in residence, it, too, never received the recognition Mary Johnston desired for it. From her will, she obviously hoped it would be made into a shrine to her famous stepmother. That never occurred. Instead, it was sold by Mary’s heirs shortly after her death and remains a private residence today.

Thanks to Anne Stewart of the Comfort Heritage Foundation, Inc. for the excerpts from The Comfort News; to Col. Bettie Edmonds of the Boerne Area Historic Preservation Society for sharing photos and information about Penacres and doing all that Courthouse deed book research; and Sally Tanselle for sharing her copies of Georgina Kendall Fellowes’ “Little Colonel” books with us.