“Mr. & Mrs. James Barnaby” and the “Barnaby Ranch”

Mr. B.H. Dane and Adeline de Valcourt Kendall-Dane

Post Oak Springs Ranch in Boerne, Texas

(B.H. Dane: – )

(Adeline Suzanne de Valcourt Kendall-Dane: June 15, 1830-February 3, 1924)

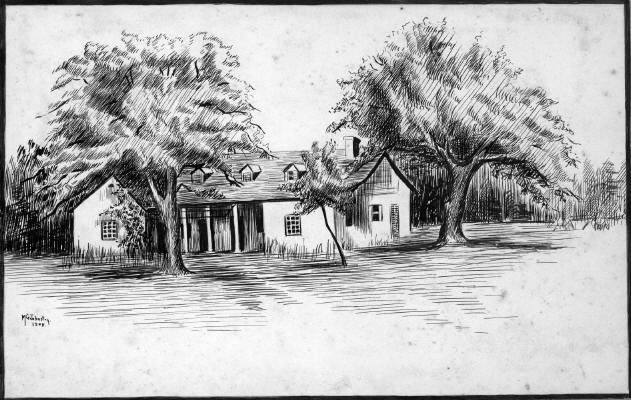

This ink sketch of Post Oaks Springs Ranch was drawn by Annie Fellows Johnston’s stepdaughter, Mary G. Johnston, in 1908.

Courtesy, Kendall Family Papers, Special Collections, The University of Texas at Arlington Library, Arlington, Texas. AR376-16-3.

Below, a later photo of the ranch, after the front porch was enclosed, courtesy of the Boerne Area Historical Preservation Society.

Annie Fellows Johnston introduces her readers to Mr. and Mrs. James Barnaby in the very first chapter of Mary Ware in Texas. She describes Mrs. Barnaby as “large and elderly” and “portly and gray-haired.” Her husband is a “stockman” and the two live on a ranch “up in the hills in the back-woods.”

As the novel progresses, more details about the fictional Barnabys emerge. They are pioneers, who had come “out from Ohio over fifty years before when (Mrs. Barnaby) was so young that she could barely remember the great prairie schooner that brought them. They had suffered all the hardships of the early Texas settlers, gone through the horrors of the Indian uprisings, and fought their way through with sturdy pioneer fortitude to the place where they could fold their hands and enjoy the comforts of the civilization they had helped to establish.”

In an “old-fashioned carriage drawn by two big gray mules, with much shining nickel-plating on their stout black harness,” the Barnabys make the seven-mile trip from Boerne to their “homelike old ranch,” where they also raised turkeys, guineas, ducks, chickens and peacocks. “A deserted cabin” at the ranch marks the spot “where Indians had once killed two Mexican shepherds” many years before. Living with them at the ranch is Sammy, an old bachelor “cousin of her husband’s who had made his home with them for years.” Sporting a “bushy gray beard made him look older than Mr. Barnaby” and “shaggy eyebrows,” he “spoke with a strong New England twang.”

Throughout Mary Ware in Texas, Mr. and Mrs. James Barnaby are depicted as true friends and in many ways, the Wares’ protectors and saviors. It is the Barnabys who come to the rescue when the Wares can’t find suitable accommodations in San Antonio by helping them rent the cottage in Bauer. It is the Barnabys who help the Wares settle in, ask the storekeepers to charge them “home prices, and not the ones usually asked of strangers,” and inform St. Boniface’s rector of their presence. It is the Barnabys who provide a jar of mincemeat and a plump hen for the Wares’ Thanksgiving dinner and the Barnabys who find some sewing projects for Mrs. Ware when the family finds itself short of money. And finally, at the end of the novel, when the Wares bid Bauer adieu, it is the Barnabys and the Rochesters http://www.littlecolonel.com/People/Rochesters they will miss most as they head for new trails.

In real life, the fictional Barnabys were inspired by some of Kendall County, Texas’ pioneers and leading citizens — the family of George Wilkins Kendall for whom the county was named. This biographical sketch of the county’s namesake is from the George W. Kendall Chapter of the NSDAR in Boerne:

Portaits of George W. Kendall

Geo. Wilkins Kendall (as he always signed his name) grew up with his parents until he was seven, then went to live with his Wilkins grandparents in Amherst, New Hampshire, and decided to stay, living with them for the next ten years. At age seventeen he set out to pursue his ambition to be a printer and writer.

For the next eleven years he apprenticed in many cities—Boston, New York, Sandusky, Cincinnati, Detroit, Chicago, Mobile, Augusta, Charleston, Washington, New Orleans and more. Horace Greeley, widely known journalist and a childhood friend of Kendall’s, was experiencing instant success with his new newspaper, the “Daily Ledger” in Philadelphia. Kendall wondered, “Why not start one in New Orleans?” In 1837 he and a partner, Francis A Lumsden, ran the first issue of the New Orleans “Picayune.” It was described as “saucy little sheet which sold for its namesake, a picayune, a Spanish coin worth 6 ¼ cents. The paper was noted for its witty, cheerful tone, its political independence, spirit of good will and emphasis on local news.

Work in the New Orleans office kept George Kendall busy until 1841, when he went as an observer and reporter on the Texan Santa Fe Expedition into New Mexico. As they approached Santa Fe, they were captured by Mexican authorities and were forced to march on foot to Mexico City, where they were imprisoned. The release of George Kendall came about a year later. His reports, written from memory, were published by “The Picayune” in a series, and later in a two-volume book set, which sold 40,000 copies.

George Kendall earned his renown as “the first modern war correspondent” during the Mexican American War. In 1846-47 he covered the battles in Monterrey and Saltillo, then Veracruz through the victory in Mexico City. His reports reached “The Picayune” faster than even the military dispatches, because he established his own relay of a courier system with horsemen, ships and telegraph. After the war, he and a French artist, Carl Nebel, jointly produced the outstanding book, The War Between the United States and Mexico, Illustrated.

Following the Mexican War, Kendall traveled to Europe with to recuperate, to see the world and to acquaint himself with the sheep industry. While in Paris, he met Adeline de Valcourt, a beautiful nineteen-year-old. They were married in France in 1849, where they made their home and had four children. Finally, in 1855 he brought them to Texas and his ranch near New Braunfels. In 1861 they moved to Post Oak Ranch just outside Boerne.

The greatest innovation Kendall gave to the sheep industry was crossbreeding the Mexican Churro ewes with the fine-fleeced Merinos, to produce a new strain with the stamina needed for the Texas hill country and the fine wool of the Merinos. Not only were they prolific in breeding, but they increased wool production dramatically. He found that the local Germans made excellent shepherds. He paid them in sheep and taught them the skills of sheep ranching. Thus, they built the sheep industry to its present day huge proportions in this area.

Geo. Wilkins Kendall died of pneumonia in 1867. His dear friend and associate in the sheep industry, Henry S. Randall, said in his obituary, “He loved Texas with an absolute devotion. He never was tired of writing or speaking in its praise. He loved its vast expanses of solitude, its majestic plains, its noble rivers, the green hills of the county named after him, and its masculine energetic population. —-George Wilkins Kendall earned his place as the father of the Texas sheep industry through hard work and energetic promotion of that industry. He did Texas and the sheep industry a great service. He fully deserves the tribute cut into his tombstone: Printer, Journalist, Author, Farmer, Eminent in All”…. Texas will deeply miss and mourn him. Perhaps she had no citizen which she could so illy afford to spare. She certainly has none who can entirely fill his place.”

Sam Woolford in a September, 1955 article that ran in the roto magazine of the “Dixie-Time-Picayune States” described why George Kendall chose the location east of Boerne on what is now rural highway 46 for his ranch:

One day he saw the gentle rise of a post-oak hill sloping down across green meadows to a creek fed to springs, a crooked creek choked with cattails and with peppery water cress. He said he wanted this to be his home.

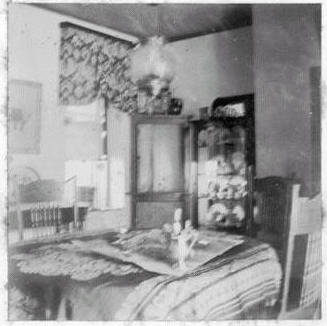

A corner of the dining room at Post Oaks Springs Ranch,

where Mary Ware and the Mallory children enjoyed a Sunday dinner

with the Barnabys and cousin “Sammy.”

Courtesy, Kendall Family Papers, Special Collections,

The University of Texas at Arlington Library, Arlington, Texas AR376-16-3

In 1861 when the Kendalls settled Post Oak Springs Ranch, Apaches, Kiowas, and Comanches were also living in the area and made frequent raids on the settlers, which continued through the mid-1870s. Just as described in Mary Ware in Texas, Post Oak Springs Ranch was raided in 1867, the year George Kendall died of pneumonia, and Indians killed two men there, Schlosser and Baptiste, according to Early Settlers and Indian Fighters of Southwest Texas by A.J. Sowell. This article from the Boerne Area Historical Preservation Society describes a raid that occurred while St. Peter’s Catholic Church was being built a few miles from the ranch:

…(Rev. Emil L.J.) Fleury, who had considerable knowledge of construction, went to Fredericksburg to hire stone masons and learn how to make lime for the mortar that would bond the stones.

He returned with two masons who agreed to work if Fleury would furnish their room and board. Fleury arranged with Mr. Phillips, who owned the inn nearby, for room and board for his men-again on credit.

Fleury and the workers quarried the limestone used for the church at the Herff Ranch. A hand-dug well was located on the right side of the church not only for the priests, but also for the animals of the ranchers who came to worship. A kiln was built on top of Kronkosky Hill for the making of lime. The young deacon cut and dressed stones along with his masons, and raised $200 to defray building costs. Parishioners Phillips, Schertz, Staffel, Dienger, Daizer, Sultenfuss, O’Grady, Kunz, Acker, Beck, Riley and Kaiser assisted the deacon along with a number of Hispanic men whose names have been lost. George Wilkins Kendall was a major contributor to the church, and records show that Casper Sultenfuss donated labor and material for the completion of the church.

At one point during the construction, Fleury was so exhausted he fell asleep on the scaffolding, and not on his pallet as he usually did. That night Indians raided the church and shot arrows into the blanket that covered Fleury’s bed. The priest was spared. His horse, however, didn’t fare as well; it was found dead behind the Philip’s Hotel where it had been tied. The church and the horse were the only items of interest to the Indians that night.

Adeline de Valcourt Kendall remained a widow for more than five years following George Kendall’s death. The 1870 Kendall County Census shows that she was living on the ranch with her daughter Louise Carolina (October 26, 1853-July 4, 1899), her mother Caroline de Valcourt (February 2, 1796-September 28, 1873) and two domestic servants, Marie and Frank Lesage. Her three other children — Georgina (1850-1847), Henry Fletcher (1855-1913) and George William Kendall (1855-1876) — are not shown on the census. On April 24, 1873, she married B.H. Dane (BIRTH-DEATH).

When the Johnston family arrived in Boerne in 1905, Mrs. Kendall-Dane was indeed elderly – she was 75 years old — and still married to B.H. Dane, who was AGE. Just as described in Mary Ware in Texas, she was also a grandmother and had three grandchildren, one by her daughter Georgina Kendall Fellowes, and two by her son, Henry Fletcher Kendall. Her two other children were dead. Georgina lived in Spokane, Washington and Henry in Oregon, which would explain why they made “annual visits” to the ranch in the story. The Johnstons must have met Georgina when she visited her mother in 1906, according to this snippet from the “Comfort News:”

June 29, 1906: Mrs. Eugene Fellowes of Spokane, Wash., is here on a visit to her mother Mrs. B.F. Dane.

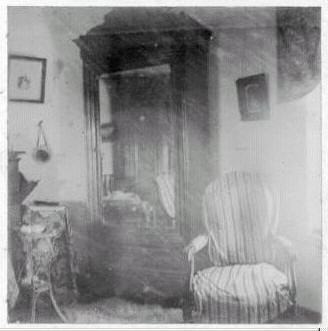

Adelina Suzanne de Valcourt Kendall-Dane’s room at Post Oak Spring Ranch,

courtesy, Kendall Family Papers, Special Collections,

The University of Texas at Arlington Library, Arlington, Texas

The real-life identity of “Sammy” in the novel is unknown. At one time, Adeline Suzanne de Valcourt Kendall-Dane’s brother, Joseph Adolphe Poirot de Valcourt (May 11, 1828-May 17, 1889), lived at the ranch, but unlike Sammy, he was French, was involved in building the Suez Canal and was a veteran of the Franco-Prussian War. He also died in 1889, 16 years before the Johnston family moved to Boerne. Sammy’s “New England twang” may mean he was related to her first husband, George Kendall Dane, who grew up in Vermont and New Hampshire.

Post Oak Springs Ranch was sold in 1908, according to these clips from the “Comfort News:”

June 29, 1906: The well known Dane lands (The old Kendall Ranch) has been placed in my hands for sale. I will sell in tracts to suit, part cash, balance at 6 per cent on time to suit. Only 3 miles from Boerne, good road. Get a home while the opportunity lasts. Come and investigate. –J.J. Graham, Sole Agent, Boerne, Texas

October 16, 1908: Mr. B.F. Dane last week sold his famous ranch of 1260 acres near Boerne. This was the home of Geo. W. Kendall after whom this county is named. The latter’s widow married Mr. B.F. Dane, and they have always made their home there. Mr. Dane’s recently failing health led to the disposal of the place, which is now the property of Mr. Ad. Ammann.

Adeline Suzanne de Valcourt Kendall-Dane died on February 2, 1924 and is buried at Boerne Cemetery with her first husband and their daughter, Louise Carolina. Also buried with them are her mother, Caroline de Valcourt, and her brother, Joseph Adolphe Poirot de Valcourt. B.H. Dane’s burial place is unknown.

MORE TO COME

Georgina Kendall Fellowes, daughter of Mrs. Kendall-Dane, standing with her son,

William H. Kendall, in front of a roadster car, September, 1929.

Courtesy, Kendall Family Papers, Special Collection,

The University of Texas at Arlington Library, Arlington, Texas AR376-16-1

Thanks to Lea M. Worcester and Cathy Spitzenberger at The University of Texas Arlington Library for their assistance with finding and scanning the images of Post Oak Springs Ranch and Georgina Kendall Fellowes with her son; to Anne Stewart of the Comfort Heritage Foundation, Inc. for the articles from the “Comfort News”; and to Sally Tanselle for finding the set of Little Colonel books once owned by Georgina Kendall Fellowes.