“Children’s Free Hospital”

Undated Photograph of Patients at the Children’s Free Hospital from the Linda Neville, Charles Kerr and Neville Family Papers, available through the University of Kentucky Libraries Special Collections and Digital Programshttp://kdl.kyvl.org/images/kukav/61m158/147.jpg

The children’s hospital in Louisville is the setting for several important scenes in “The Little Colonel’s Holidays.” In Chapter XIV, “Lloyd Makes A Discovery,” The Little Colonel and the Walton girls are delivering flowers to the patients and discover Dot, Molly’s long-lost sister, in one of the hospital wards.

(Molly was the orphan girl who lived with the Appletons at the Cuckoo’s Nest, Betty’s rural childhood home. The sad tale of how she came to be an orphan and her subsequent separation from her sister, Dot, is told in Chapter VI, “Molly’s Story.”)

In the next chapter, XV, “A Happy Christmas,” Lloyd, Kitty, Allison and Elise deliver 20 decorated Christmas trees to the children’s hospital, Dot and Molly are at last reunited and spend Christmas day together in a private room at the hospital, and Dot dies with her sister at her bedside as the last Christmas candles flicker out.

[Left: Mary Lafon]

[Left: Mary Lafon]

In 1901, when “The Little Colonel’s Holidays.” was published, the Children’s Free Hospital in Louisville had been caring for sick and injured children for nine years. Four founders are credited with making the hospital – the first medical facility in the city to be dedicated exclusively to the treatment of children – a reality: social activists Mary Lafon and Hallie Quigley, who both lived near Central Park; Dr. John A. Larrabee, president of the American Medical Association’s section on children’s disease and of the Louisville Hospital College of Medicine; and Dr. Ap Morgan Vance, a pioneer in both surgery and orthopedics.

The hospital was originally located in a refurbished town house at the corner of E. Chestnut and Floyd Streets, within walking distance of Louisville City Hospital and the Louisville Hospital College of Medicine. It remained in the town house until 1910, when a new building was erected and attached to the house with an annex.

Eight children, two in wheelchairs and one on crutches, sitting outside; “Linda Neville’s patients on Children’s FreeHospital lawn in Louisville” from the Linda Neville, Charles Kerr, and Neville Family Papers, 1847-1959, available through the University of Kentucky Libraries Special Collections and Digital Programs http://kdl.kyvl.org/images/kukav/61m158/162.jpg

Five-year-old James Radford Duff, or “Little Radford” as he was affectionately known, was the hospital’s very first patient, when he was admitted on January 17, 1892. Annie Fellows Johnston’s description of Micky O’Brady inChapter XIV of “The Little Colonel’s Holidays” bears some resemblance to Little Radford:

Four little girls, each with her arms full of great red roses, with leafy stems so long that it seemed the whole bush must have been cut down with them, passed down the room, leaving one at each pillow.

“My Aunt Elise sent them,” said the smallest child, pausing at the first white bed. “She asked us to bring them ’cause she couldn’t come herself. They’re American Beauties and they always make me think of my Aunt Elise.”

“She must be a dandy, then,” was the response of Micky O’Brady, on whom she bestowed one, taking it up awkwardly in his left hand. His right one was still in a sling, and one leg had just been taken out of a plaster cast, for he had been run over by a heavy truck, and narrowly escaped being made a cripple for life. Elise stopped to question him about his accident, and found that despite his crippled leg a pair of skates was what he wished for above all things.

“Kosair Children’s Hospital: A History 1892-1992,” pages 12-14, provides the following description of Little Radford’s medical ordeal:

…The child was from Big Stone Gap, a Virginia village high in the mountains on the southeastern Kentucky border. Doctors there had pronounced him a ‘hopeless cripple,’ a frightening verdict. In Little Radford’s hometown, disabled children were alternately coddled and despised.

Already suffering from tuberculosis, he had been jumping on a mattress at Duff House, his parents’ inn, when a bedspring gave way. He had damaged his hip….

…On January 27, ..Vance…properly set the damaged hip and leg, bracing them in a cast. Then the child was released to the watchful, loving, no-nonsense care of Miss Bridgers (a young nurse at the hospital), who was told to keep him absolutely still. There were no powerful antibiotics in 1892. The hope was that the tubercular infection would die down.

It seemed to work. Six months later, suntanned and walking, Radford went home for vacation from the hospital, warned to use his crutch. It was imperative that no weight be put on the hip. Released to the mountain summer…, the child happily ran and played. By the time the vacation was over, the tuberculosis in his hip had flared dangerously.

…Vance frowned when he saw him and scheduled full surgery…Then he put Radford’s leg in a cast.

The slow process of recovery began. The child was not allowed to get out of bed for six months. Throughout the spring and most of the summer, the nurses wheeled him out into the sunshine and fresh air of the backyard. They talked and sang to him, taught him games…

Radford left Children’s Free Hospital in 1894, when he was seven, cured of tuberculosis and walking.

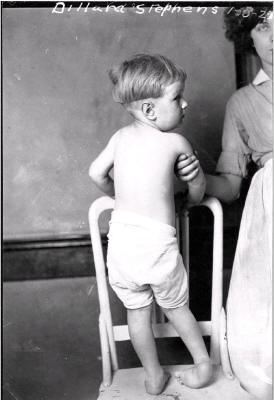

[Left: Little boy with crippled leg standing in chair] ; “Linda Neville’s Crippled patient (Dillard Stephens), photographed at the Childrens’ Free Hospital in Louisville (Chestnut Street), Jan., 8, 1923 from the Linda Neville, Charles Kerr, and Neville Family Papers, 1847-1959, available through the University of Kentucky Libraries Special Collections and Digital Programshttp://kdl.kyvl.org/images/kukav/61m158/417.jpg

[Left: Little boy with crippled leg standing in chair] ; “Linda Neville’s Crippled patient (Dillard Stephens), photographed at the Childrens’ Free Hospital in Louisville (Chestnut Street), Jan., 8, 1923 from the Linda Neville, Charles Kerr, and Neville Family Papers, 1847-1959, available through the University of Kentucky Libraries Special Collections and Digital Programshttp://kdl.kyvl.org/images/kukav/61m158/417.jpg

Children’s Free Hospital relied on volunteers and gifts for its existence. An all-volunteer hospital circle served as the administration and public relations staff; recruited volunteers who comprised 99 percent of the hospital’s work force during its first 27 years of operation; and met monthly to sew the vast quantities of sheets, towels and diapers the hospital required. Many of the volunteers came from the Warren Memorial Presbyterian Church, which Lafon and Quigley both attended, as well as the Culbertsons and most likely, the Lawtons, when they were living at 1511 S. Fourth Street following General Lawton’s death in the Spanish American War.

Also involved was the recently formed Woman’s Club of Louisville. While we do not know if Annie Fellows Johnston was ever a member, a newspaper clipping from a scrapbook at Louisville Free Public Library shows that she read a story she wrote called “Ben’s Thunderstorm” at one of their Saturday morning children’s ‘programmes’ in 1922.

Annie Fellows Johnston’s relationships with people who were heavily involved with the hospital may have been the dominant factor in her decision to use it in “The Little Colonel’s Holidays.” Louise Culbertson (“Aunt Elise”) was a member of the Woman’s Club and also served on the board of the Children’s Free Hospital according to her obituarypublished in the September 13, 1938 “Courier-Journal.” Through her longstanding friendships with Louise Culbertson’s mother, Annie Craig (Grandmother McIntyre), and sister, Mary –”Mamie” Lawton (Mrs. Walton), the author undoubtedly was kept informed of the hospital’s mission and progress. Another personal friend, Dr. Gavin Fulton, was “one of the initial supporters of the founding of Children’s Hospital” and “among the first doctors on its staff,” according to his obituary, published in the September 10, 1953 “Courier-Journal.” The two became friends when Dr. Fulton was practicing medicine in Pewee Valley between 1896 and 1903. Mortuary records show he was the attending physician for her stepdaughter, Rena Eaves Johnston, when she died of appendicits in September 1897. In 1900, Annie Fellows Johnston dedicated “The Story of Dago” to him (re-released in 1931 as “The Three Tremonts”) and called him the “best of physicians and friends.”

The scenes in “The Little Colonel’s Holidays” where the Walton girls and the Little Colonel bring flowers and Christmas trees to cheer young patients were common occurrences from the time Children’s Free Hospital opened its doors, according to “Kosair Children’s Hospital: A History 1892-1992,” page 15:

Contributions poured in, an unending river of flowers to brighten the wards, coal, clothing, butter, Easter toys, Christmas trees, gowns, hemming, watermelons, apples, three rabbits here, a Thanksgiving dinner there, seashells from the Florida coast, scrapbooks made by seemingly half the church and temple class schools in town. The young ladies of Kentucky Home School for girls made sandwiches.

More than a century later, Children’s Free Hospital has evolved into Kosair Children’s Hospital, Kentucky’s only free-standing, full-service pediatric care facility. Care is no longer free and the staff is no longer volunteer. However, the tradition of donating decorated Christmas trees has continued through the Children’s Hospital Foundation’s annual Festival of Trees & Lights.

Many thanks to Norton Healthcare for sending us a copy of “Kosair Children’s Hospital: A History 1892-1992.”

Page by Donna Russell