“Henry W. Lawton, the Soldier & the Man”

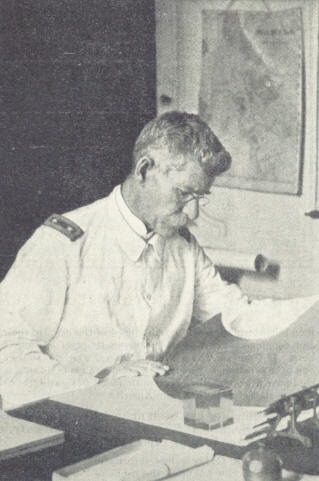

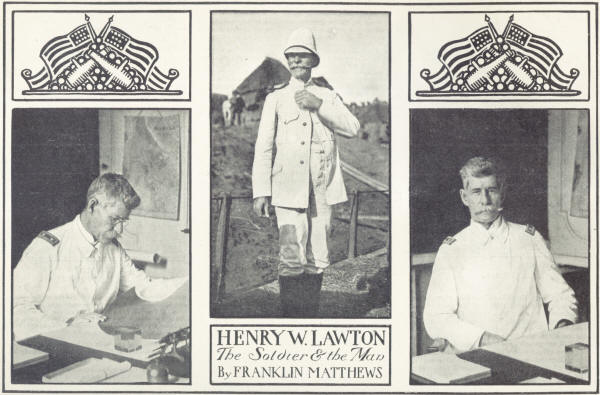

Two views of General Lawton at his desk, Philippine Islands 1899

From Harper’s Weekly, January 6, 1900

“Henry W. Lawton, the Soldier & the Man“

Franklin Matthews

THE people of the United States were shocked on December 19, when a cable message from General Otis, in Manila, to the War Department, announced the death in action on the day before, at San Mateo, in the island of Luzon, thirteen and a half miles northeast, of Manila, of Major-General Henry W. Lawton, the foremost fighter of the American army. General Otis’s despatch closed with the words,” Great loss to us and to his country.”

For nearly forty years Lawton had been in the army, and no man wearing its uniform had done harder, more brilliant, and more dangerous work. Until within a year and a half the country scarcely knew him. The people had heard of him thirteen years ago as a fearless Indian-fighter, but that work was wellnigh forgotten. If it had been asked who it was, away back in the eighties, had captured the devilish Apache leader Geronimo, probably the most cruel, crafty, and treacherous Indian this country ever had to deal with and punish, not one person in a thousand outside of the army could have recalled Lawton’s name. After he had taken El Caney in the Santiago fight of July 1, 1898, the country rubbed its eyes and learned to respect and admire him as a military man of broad scope, a clever tactician, a persistent fighter, a man of indomitable bravery and will power—a real general. Later, when he went to the Philippines, and like a whirlwind swept the Filipinos before him, scattering them like chaff, running down and capturing their leaders until even Aguinaldo himself, stripped of his escort, family, and personal followers, was compelled to flee into the mountain fastnesses in disguise, then it was that at last the American people found out Lawton, and began to love him and estimate him at his true worth.

Lawton was “only a soldier,” as he said himself, in the presence of the President, to an audience in Montgomery, Alabama, after the Cuban campaign had closed—but, such a soldier! On the trail of a treacherous foe he was a veritable blood-hound. In the presence of an enemy who would fight true and bravely he was a lion-hearted Richard. With a conquered opponent he was just, magnanimous, and even gentle. Fear in battle he never seemed to know. He did not scorn the enemy’s bullets; his mind was keyed to a higher pitch. He wanted to win. Where the danger was greatest, there was Lawton on the outermost edge of the fighting line. He braved danger not because he was fool-hardy, not because he wanted to win promotion, and probably not so much to set an example to his men, as because he could do no other thing and be himself.

Perhaps the greatest tribute that can be paid to Lawton is that he never ordered the humblest private to endure privations and dangers he did not share himself. He always led his men. The wonder was not that he was killed at San Mateo, but that he was not killed before. From a military point of view he was fortunate in his life and fortunate in his death. The “glory of dying in battle” was his. He died as he would have chosen to die, had the choice been his. He was the only general officer killed since hostilities with Spain and the Filipinos began, and when the fatal bullet pierced his heart the clerks were making out his commission as a Brigadier-General in the regular army, his country’s reward for faithful work as a soldier. Truly his death was a “great loss to his country.”

Perhaps the greatest tribute that can be paid to Lawton is that he never ordered the humblest private to endure privations and dangers he did not share himself. He always led his men. The wonder was not that he was killed at San Mateo, but that he was not killed before. From a military point of view he was fortunate in his life and fortunate in his death. The “glory of dying in battle” was his. He died as he would have chosen to die, had the choice been his. He was the only general officer killed since hostilities with Spain and the Filipinos began, and when the fatal bullet pierced his heart the clerks were making out his commission as a Brigadier-General in the regular army, his country’s reward for faithful work as a soldier. Truly his death was a “great loss to his country.”

Lawton was in his fifty-sixth year, and since April, 1861, had been a soldier, with the exception of a short time after the civil war closed, when he entered the Harvard Law School, in doubt whether a commission in the regular army would be made out for him. He was a remarkable man in appearance, a splendid target, and it was strange that no bullet found him sooner. He was six feet three inches tall, and he weighed more than two hundred pounds. His jaw was square, his lips thin, his eyes gray, his cheek-bones prominent, his forehead high and narrow; his hair was tinged with gray and his mustache was nearly white. He was not handsome, but his striking face displayed his characteristics minutely. Thick as to his chest, long as to arms and legs, erect and straight in his carriage, he was supple as a youth, and his giant frame matched his courageous heart. He could go without food and sleep for days, and there seemed no limit to his tireless energy. He was of violent temper when he was aroused, and he did not mince his words when angered. A strict disciplinarian, his men loved him and obeyed him implicitly. He was simply one of them. They endured hunger and thirst, and even walked the shoes off their feet, because Lawton wanted them to do so rather than give up. The Indians called him “Man-who-gets-up-in-the-night-to-fight,” “Charging Buffalo,” and “Mad Bear,” and those names were eminently fit for him. He was big in frame, big in heart, and knew nothing, cared for nothing, but devotion to his country and her arms.

United States Senator Beveridge was quoted, the day after Lawton’s death, as saying that Lawton said to him one day last summer while at the front in the Philippines:

“I suppose I shall be killed some day. But that is part of a soldier’s profession. We who go to be soldiers of the republic understand this thoroughly.”

There was nothing showy in Lawton’s manner of command. He did not like dress parades. Senator Beveridge, who was with him daily for several weeks in the Philippines, says that when he ordered the South Dakota regiment into action al Taytay he rode quietly across the field and said to the colonel, “Get your men into town’” To the Twelfth regulars’ major he said, “Get your men on the move, Major!” Then he went. with them. When he saw his men in danger he warned them, but took no thought of himself. He had escaped so often himself that it seemed as if he bore a charmed life; but he did not think of that. Whenever possible, he did his own scouting. He wanted to see himself where the would have to send his men. In the dead of night he stole up the Pasig River into Laguna de Bay, in peril every minute of the trip. He would climb into a church belfry at. daybreak to spy out the land. He would not listen to withdrawal once he had begun to light. When word came from General Shafter at El Caney to stop fighting. after Lawton had been at it for eight hours, and to go to the support of the troops at San Juan Hill, he shouted, “I can’t quit.” Then, while the aide went back for written orders, he gave the command, “Forward as skirmishers!” and in half an hour carried the Spanish strong-hold. In the later days of the Philippine fighting he nettle himself especially conspicuous by wearing a white helmet, and on the day he was killed he made himself the better mark by walking about in a long yellow rain-coat. He seemed unconscious of his increased danger because of his costume, and would not, sell his helmet to one of his subordinates who offered him $15 for it, in the desire to lessen the general’s chances of being hit.

It is impossible to crowd into a short space any adequate account of what. Lawton did as a soldier. He was eighteen when he left college to enlist as a sergeant in Company E of the Ninth Indiana ninety-days regiment, immediately after Fort Sumter was fired upon. On August 21, his first enlistment having expired, he became a First Lieutenant in the Thirtieth Indiana, and he came out of the war in 1865 a Lieutenant-Colonel and a brevet Colonel. He fought at Shiloh and Corinth and Chickamauga. He went on the march through Georgia. At Atlanta he attracted especial attention by his bravery. He won his medal of honor “for gallant and meritorious service.” He led a charge of skirmishers against the enemy’s rifle-pits and captured the place. Twice he resisted desperate attacks of the enemy to retake the ground. He fought also at Philippi, Laurel Hill, Cheat River, and was in many engagements under Grant, Sherman, Buell and Rosecrans. All those officers knew him and his work well, and Sherman and Sheridan were among his warmest supporters in his effort, after the war was over, to secure it commission in the regular army.

Lawton secured his commission as it Second Lieutenant on July 28, 1866, in the Forty-first Infantry. He became a First Lieutenant on .July 31, 1867. In 1869 he was transferred to the Twenty-fourth Infantry. In 1871 he was sent to the Fourth Cavalry, and at that time it has been said that General Mackenzie said of him: “I like that new Lieutenant of mine, Lawton. Unless I am very wide of the mark, he will prove a great soldier.” Lawton served in the many Indian campaigns of the West for twenty years. He fought against the Sioux, the

Utes, and other tribes. He did not become a Captain until 1879, and it was not until 1886 that his great chance came. The bloodthirsty Apaches under Chief Natchez, but really under the lead of the crafty and cruel medicine-man Geronimo, were on the war-path. General Crook had failed to catch the band. The War Department thought one of his messages insolent, and General Miles was sent out to take Crook’s place. Miles thought the way to catch Geronimo was to pursue him with a band as tireless as that of the Indians themselves, and with a man at the head who would die rather than give up. He selected Lawton for this work.

It was a terrible task, but Lawton succeeded. Once he had Geronimo in his possession, but at night the Indian and his followers broke away after killing several soldiers on guard. Enraged beyond restraint, Lawton started on the trail again, a veritable fury. Across desert and mountain, through ravines and over plains, the hunt went on without food or drink for days sometimes, the pursuers kept on. There was no rest for Geronimo. The soldiers became barefoot. They killed their mules for food, and at last, after a. chase of 1386 miles, the wily Apache was cornered in the mountains of Mexico, into which our troops had penetrated by special permission.

Geronimo surrendered on condition that his life and those of his followers should he spared. The triumphant Lawton gave his pledge, and the government kept it. He brought the captured Indians to San Antonio, and this description by a fellow-officer, printed in the New York Times of December 20, not only pictures the scene of their arrival graphically, but reveals the manner of man Lawton was, and shows what his campaigning meant:

He stood on the government reservation at San Antonio, surrounded by the tawny savage band of Chiricahua Apaches whom he had hunted off their feet. The squat figures of the hereditary enemies of the whites grouped about him came only to his shoulders. He towered among them, stern, powerful, dominant—an incarnation of the spirit of the white man, whose war-drum had beaten around the world. Clad in a faded, dirty fatigue-jacket, a greasy flannel shirt of gray, trousers so soiled that the stripe down the leg was barely visible, broken boots, and a disreputable sombrero that shaded the harsh features burned almost to blackness, he was every inch a soldier and a man. To the other officers at the post the Indians paid no sort of attention. To them General Stanley and his staff were so many well-dressed lay figures, standing about as part of a picture done for their amusement; but the huge, massive man with the stubble on his chin had shown them that he was their superior on hunting-grounds that were theirs by birthright, and they hung upon his lightest word.

Then came a life of comparative ease for Lawton. In 1888 he was made a Major and Inspector-General, and he lived most of the time in Washington until the Spanish war came. He secured a place in the line in the volunteer forces, and fought as a Brigadier-General in command of the division that took El Caney. His work there is too fresh to need detailed narration. His health became impaired after the fighting, and he took a rest. He had been made a Major-General of Volunteers; on January 19, 1899, he left on the transport Grant for Manila. He did not get into the fighting in the Philippines until April 22, but when he started he was a whirlwind. He fought twenty-two fights in twenty days. He captured twenty-eight towns. He killed 400 of the enemy. He took Santa Cruz, San Rafael, and the insurgent capital, San Isidro. President McKinley sent him his especial congratulations for his work when the rainy season had stopped the fighting. Readers of HARPER’S WEEKLY who have followed its special correspondence from the Philippines need no recapitulation of his more recent work. His sweeping march to the north in Luzon, up beyond Cabanatuan and Arayat, his swift, irresistible advance, the capture of members of Aguinaldo’s family and cabinet, the scattering of the insurgents, and the flight of Aguinaldo himself marked Lawton’s charge. His men again were barefoot, and again they lived off the country. For days he and his soldiers were missing they were on the pursuit with relentless vigor.

Then came a life of comparative ease for Lawton. In 1888 he was made a Major and Inspector-General, and he lived most of the time in Washington until the Spanish war came. He secured a place in the line in the volunteer forces, and fought as a Brigadier-General in command of the division that took El Caney. His work there is too fresh to need detailed narration. His health became impaired after the fighting, and he took a rest. He had been made a Major-General of Volunteers; on January 19, 1899, he left on the transport Grant for Manila. He did not get into the fighting in the Philippines until April 22, but when he started he was a whirlwind. He fought twenty-two fights in twenty days. He captured twenty-eight towns. He killed 400 of the enemy. He took Santa Cruz, San Rafael, and the insurgent capital, San Isidro. President McKinley sent him his especial congratulations for his work when the rainy season had stopped the fighting. Readers of HARPER’S WEEKLY who have followed its special correspondence from the Philippines need no recapitulation of his more recent work. His sweeping march to the north in Luzon, up beyond Cabanatuan and Arayat, his swift, irresistible advance, the capture of members of Aguinaldo’s family and cabinet, the scattering of the insurgents, and the flight of Aguinaldo himself marked Lawton’s charge. His men again were barefoot, and again they lived off the country. For days he and his soldiers were missing they were on the pursuit with relentless vigor.

Then quickly Lawton returned to Manila, and on Monday night, December 18, in a driving storm, he set out for San Mateo. General Otis at first forbade the movement, on account of the weather, but Lawton pleaded with him, and the went to his death. He was killed as his troops were taking the town, and after it was all over they bore his body to a building, and one by one filed by his corpse for a last look at his face, the tears running down their cheeks.

Then quickly Lawton returned to Manila, and on Monday night, December 18, in a driving storm, he set out for San Mateo. General Otis at first forbade the movement, on account of the weather, but Lawton pleaded with him, and the went to his death. He was killed as his troops were taking the town, and after it was all over they bore his body to a building, and one by one filed by his corpse for a last look at his face, the tears running down their cheeks.

No record of Lawton should be made without mention of a dramatic incident that followed his death. He had been quoted far and wide as saying that he wished “this accursed war” would stop. His friends say he really used the expression, “this damned war.” It was interpreted to mean that he did not sympathize with the war on the Filipinos. He was entirely misunderstood. As if it were a voice from the grave, former Minister to Siam, John Barrett, read a letter from him, written in November last, at the New England dinner in New York on December 22. He wrote:

I would to God that the whole truth of this whole Philippine situation could be known by every one in America as I know it. If the so-called anti-imperialists would honestly ascertain the truth on the ground and not in distant America, they whom I believe to be honest men misinformed, would be convinced of the error of their statements and conclusions, and of the unfortunate effect of their publications here. If I am shut by a Filipino bullet, it might as well come from one of my own men, because I know from observations, confirmed by captured prisoners, that the continuance of fighting is chiefly due to reports that are sent out from America.

This summary has been made of Lawton’s genius by the military friend whom I have quoted already, and with eloquent force it marks the man:

The man of El Caney is the reincarnation of some shining, helmeted, giant warrior who fell upon the sands of Palestine in the First Crusade, with the red blood welling over his corselet and his two-handed battle-sword shivered to the hilt. The race type persists unchanged in eye, in profile, in figure. It is the race which in all the centuries the Valkyrs have wafted from the war decks—the white-skinned race, which, drunk with the liquor of battle, reeled around the dragon standard at Senlac, which fought with Richard Grenville, which broke the Old Guard at Waterloo, which rode up the slope at Balaklava, which went down with the Cumberland at Hampton Roads, which charged with Pickett at Gettysburg—the race of the trader, the financier, the statesman, the inventor, the colonizer, the creator, but, before all, the fighter.

General Lawton leaves a widow and four children—one boy and three girls. He never had time to accumulate property. Without doubt Congress will provide a suitable pension for his widow, and already sympathetic friends are raising a fund to place her beyond the possibility of want. No grand monument can add honor to Lawton’s memory. Such a testimonial, however, could honor the country for which tie fought and died.

Franklin Matthews

From Harper’s Weekly, January 6, 1900