Mary “Miss Mamie” Gardener Johnston

(November 16, 1872- July 16, 1966)

Annie Fellows Johnston’s Stepdaughter

Real-Life Model for Joyce Ware in the “Little Colonel” Stories

An Artist in Her Own Right

Mary Johnston as a young woman, posing for a photo taken by her dear friend, Kate Matthews.

Kate Matthews Collection, Photographic Archives, Ekstrom Library, University of Louisville

Mary Johnston, also known as Miss Mamie in later years, was Annie Fellows Johnston’s step-daughter, and was the basis for the character of “Joyce Ware” in the series of books. Annie Fellows Johnston gave the “Little Colonel” character “Joyce Ware” Miss Mamie’s long blonde hair and artistic abilities. As noted by the author in later years:

After John’s death it was so lonely at Penacres that we came back to Kentucky to live. We have been back in the valley now for seventeen years. Life is intensely interesting wherever Mary is, because she makes it so. She is an artist, a wonderful gardener, and the dearest daughter anybody ever had.

She made some of the illustrations in the original “Little Colonel” book and designed the first Paper Doll book. It is through her unselfishness that I have had leisure to write. I drew upon some of her experiences in creating Joyce Ware.

Annie Fellows Johnston

“The Land of the Little Colonel,” 1929

Joyce Ware makes her debut as a major character in the second book of the “Little Colonel” series, “The Gate of the Giant Scissors,” published in1898. When Annie Fellows Johnston wrote this tale, she never intended it as a sequel to “The Little Colonel,” published three years earlier. However, with the first “Little Colonel” story’s immense popularity, she later incorporated Joyce into the series with the 1900 publication of the fourth book, “The Little Colonel’s House Party.” Whether this was her own idea or at the behest of her publisher, L.C. Page and Company, we can’t say.

“The Gate of the Giant Scissors” is largely based on Annie Fellows Johnston’s experiences on an 1897 trip to Europe. In her autobiography, “The Land of the Little Colonel,” she describes how the opportunity to travel abroad came about:

I …was beginning to consider what I should do next, when I had a telegram from Aunt Florence asking me to meet her in Oconomowoc. I knew she was there visiting some relatives, but could not imagine why she should summon me to join her…I found that my hosts wanted someone to take their eighteen-year-old daughter, Eleanor, abroad; and Aunt Florence had suggested me. I stayed there several days talking the matter over with them, and finally decided to accept their offer. Indeed, it seemed as if Providence had closed every other road to me and had opened up this one. It was the only thing left to do.

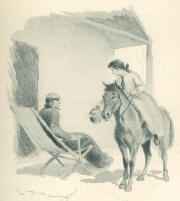

Joyce Ware perched in a tree and feeling homesick

during her travels with her Cousin Kate in France.

Illustration by Etheldred B. Barry from “The Gate of the Giant Scissors”

Her autobiography also notes many of the scenes in the novel were based on real-life events that occurred during her travels with Eleanor, including their experiences with the Little Sisters of the Poor and the Noel fête for the village children in the final chapter. In this tale, at least, it appears that the model for Joyce Ware was most likely Eleanor, with Annie Fellows Johnston herself serving as the model for Cousin Kate.

Not until “The Little Colonel’s House Party” does Joyce’s character begin to resemble Annie’s stepdaughter, Mary. In Chapter I, we learn several important things about Joyce: she is from Plainsville, Kansas – “the little western village” referred to in “The Gate of the Giant Scissors;” her mother was a classmate of Mrs. Sherman’s at the Lloydsboro Seminary; and she is an artist:

“…she draws beautifully. Mothah says that her sketches are fine, and that Joyce will be a real artist when she is grown.”

When Lloyd’s invitation to the house party reaches Plainsville in Chapter IV, we learn more about her family situation at the Wares’ little brown house – the tedium of her life, her daily housekeeping duties, the lack of money:

“If I wasn’t at home,” she said to herself, “I should think that I am homesick, for I feel the way I did that day up in Monsieur Gréville’s pear-tree in the old French garden. Then I was tired of France and everything foreign, and would have given all I owned to be back in America. Now I am here with mother and the children, but still I am as unhappy and dissatisfied as I was then. I wonder why!”

It had been less than a year since Joyce had had that wonderful winter in Touraine with her cousin Kate, but it seemed such a long, long time ago, in looking back upon it. She had settled down into the common humdrum round of duties so completely that sometimes it seemed to her that she had never been away at all; that she must have dreamed that year into her life, or read about it as happening to some other girl.

As she stood with her face pressed against the window-pane, the noise in the dining-room suddenly ceased, and Mary came into the kitchen, followed by the rest of the menagerie. “I’m tired of being a lion,” she said, wiping her flushed little face with the sleeve of her apron, and shaking back her funny little tails of hair tied with red ribbon, that were always bobbing forward over her shoulders.

“I’ve roared till my throat is sore, and I’m hungry. Isn’t supper most ready, sister?”

Joyce glanced at the clock. “It’ll be ready in ten minutes,” she answered, and returned to her survey of the back yard.

“I wish that we were going to have dumplings for supper to-night,” said Holland, “and turkey and sausages. Don’t you, Mary?” He snuffed hungrily at the saucepan on the stove.

“No,” said Mary, pausing thoughtfully, as if considering a weighty matter. “I’d rather have ice-cream and chocolate cake. If I had a witch with a wand that’s what I’d wish for supper to-night. Wouldn’t you, sister?”

Joyce turned away from the window and lifted the lid from the kettle in which the stew was bubbling. “I don’t know,” she said, gazing dreamily into the depths of the savoury stew. ” If I had that old witch with a wand that you are always talking about, I’d not stop simply with something to eat. I would wish myself back in Tours, with Madame sweeping down to dinner in her red velvet gown, and the candlelight shining on the cut glass and silver. I’d wish for dinner to be served elegantly in courses as Henri did it there every night, and I’d hear old Monsieur making his little jokes over the walnuts and wine. And afterward there wouldn’t be any dishes for me to wash, as there are here, and at bedtime Marie would come with my candle and untie my slippers and brush my hair. Oh, it’s so nice to be waited on! You don’t know how I miss it sometimes. It is horrid to be poor.”

Mary and Holland listened in flattering silence. They had great respect for their thirteen-year old sister, who had been across seas and visited old chateaux where kings and queens once lived. She was the only child in Plainsville who could boast the distinction of having been abroad, and there was a glamour about it that enchanted them. They were never tired of hearing of her adventures.

“It’s horrid to be poor,” she said again, clapping the lid on the kettle. “I hate to live in a little crowded-up house, and spoil my hands with dust and dish-water, and do the same things year in and year out.”

Joyce stopped suddenly, wishing that she could unsay that last speech, for the little mother had come into the kitchen in time to hear it. There was a pained expression on her face.

“I am afraid my bird of passage will never be satisfied with the little home nest again,” she said, sadly.

“Oh, mother, I didn’t mean it as bad as it sounds; truly, I didn’t,” cried Joyce. “You know that usually I am as contented as a cricket; but I don’t know what is the matter with me to-day. It must be the weather.”

Just then there was a stamping on the porch outside, and the violent flapping of an umbrella to rid it of the raindrops clinging to it.

“Jack!” shouted Mary, rushing to the door, with Holland and the baby tagging at her heels. “A letter for Joyce!” they called in chorus the next instant, all straggling back after the oldest brother as he bore it triumphantly unto the kitchen.

“From Lloydsboro Valley,” announced Joyce, and Mrs. Ware’s face lighted up with one of her rare smiles.

“Ah, I knew it was coming,” she said, “and I am sure it will prove an antidote for your blues. I had a letter from the same place last week, and I’ve been in the secret ever since.”

“What secret?” demanded Mary, her eyes round with curiosity, and Jack echoed the question.

“That Joyce was to be invited to a house party in June, back in ‘My old Kentucky home.’ The invitation is from one of my old school friends. There were three of us,” she went on, in answer to the look of eager interest in Mary’s eyes. “Three girls who grew up together: Joyce Allen (your sister is named for her), Elizabeth Lloyd, and myself. And now our little daughters are to meet in the same dear old valley where we played together and grew up together and learned to love each other like sisters. I hope they will become as dear friends as we were.”

Joyce looked up from her letter, her face aglow with joyful surprise. “Oh, mother!” she cried, “do you really mean it? Is it possible that I am to go? How can you afford it?”

Mrs. Ware motioned toward the envelope lying at Joyce’s feet.

“Look again,” she said, “and you will find that Mr. Sherman has sent a pass. As for the clothes, well, your , witch with a wand’ has come to the rescue again.”

“Cousin Kate?” gasped Joyce.

Mrs. Ware nodded. “What would you think if I were to tell you that there has been a box hidden away in my closet for nearly a week, waiting for this letter, which I knew was on its way, and inside are the very things you need to complete your summer outfit? There is a new hat, for one thing, and material for several very pretty dresses.”

Later, in Chapter VII, we see her through Betty’s eyes:

JUNE 6th.

Joyce came to-day on the noon train. She has the blue room across the hall from mine. It suits her for she is a blonde like Lloyd, but her hair doesn’t curl any. It is just soft and wavy, and hangs in two long braids below her waist. Her eyes are gray with long dark lashes, and while she isn’t exactly pretty, she has a face that you like to keep looking at. It is so bright and jolly, as if she was always thinking funny things, and having a good time all to herself.

She came all the way alone, and didn’t mind it a bit although she had to change cars twice, and was all night on the sleeping-car. She brought a sketch book in her satchel that is almost full of pictures she drew on the train. There is one that is so funny. It is the head of an old man, gone to sleep with his mouth open. She wrote under that one, “As others see us.” Then she drew two cunning babies playing peek-a-boo in the aisle. She called that “Innocence abroad.” There are ever so many more that godmother says are really clever, and remarkably well done for a girl of thirteen. I thought they were perfect.

Born November 16, 1872, Mary Gardner Johnston was the oldest of William Levi and Hallie (Eaves) Johnston’s three children. She was followed by Rena Eaves in 1878 and John in 1881.

In several important aspects, her early life paralleled her future stepmother’s. Both were minister’s daughters and both lost a parent during childhood. In 1883, at the age of 11, Mary lost her mother, Hallie, to consumption. Annie lost her father, Rev. Albion Fellows, in 1865, while he was pastor at the Trinity church in Evansville, Indiana. She was two years old when he died.

During her mother’s final illness and until her father’s marriage to Annie Julia Fellows on October 11, 1888, Mary and her siblings were sent to Pewee Valley to live with their mother’s sister, Rena, and brother-in-law, Albert W. Burge, at Delacoosha. According to her obituary, Mary was 10 years old when she moved to Pewee Valley, making Rena about 4 and John only a year old. The three Johnston children spent five years with their aunt and uncle, and even after the family was reunited in Evansville, “The girls went back every summer…” Annie Fellows Johnston wrote in her autobiography.

Unlike the Johnston children, Annie spent her childhood with her mother and sisters, Lura Charlotte, b. November 2, 1857, and Albion Mary, b. April 8, 1865 in the family home in McCutchanville, Indiana.

The Ware family bears similarities to both women’s childhoods. In the stories, Joyce is the oldest, just as Mary Johnston was the oldest of the three Johnston children and probably shouldered some responsibility for their day-to-day care as her mother’s health deteriorated. Like Annie Fellows Johnston, however, Joyce Ware lost her father and lived with her widowed mother.

Joyce Ware’s resemblance to Mary Johnston lies primarily in her artistic abilities and appearance, particularly her long blonde hair, a memorable feature also noted by her neighbor at Bemersyde, Cary Hoge Mead, many years later in her memoirs, “Sunshine and Shadow:”

Miss Mamie had curly, golden hair which she wore parted in the middle and caught up in a bun on the back of her head.

According to “The Genealogical History of The McGaffey Family, Including also the Fellows, Ethridge and Sherman Families,” published by George W. McGaffey in 1904, Annie Fellows Johnston maintained the family home on Oak Street in Evansville for five years after her husband died and her stepchildren “…were as dear to her as though they had been her own.” However, by 1897, economic necessity forced the author to break up their Evansville home and travel, according to her autobiography, “The Land of the Little Colonel:”

In September, 1897, we came to a turn in the road where we could see only one step ahead at a time. Rena joined Mary in Pewee Valley; I sold or stored our household goods and took John up to Highland Park to put him in the military school there. After leaving him at the school I made a short visit to some cousins in Evanston. While there, it was suggested that I write a story of the Deaconess movement. It was much like Jane Addams’ work at the Hull House.

Though Albert Burge came from money – his father was Louisville tobacco tycoon Richardson Burge — there are hints that all was not well in the Burge household. An 1877 profile written about Richardson Burge in the “Biographical Encyclopedia of Kentucky of Dead and Living Men of the Nineteenth Century” reported that Albert joined his father in the family business in 1870. Yet, “The Village of Anchorage,” by Samuel W. Thompson, Anchorage Civic Club, 2004, pg. 75 noted that it was Richard Mentor Johnston, married to Albert’s older sister Emma Moore in 1876, who ended up with the family business:

…When the successful tobacco merchant died in 1878, his son-in-law took over the Enterprise Tobacco Warehouse Company…

In “Mrs. Albert Dick Remembers” by Yvonne Eaton, which ran in the August 7, 1969 issue of the “Courier-Journal,” Hattie Cochran Dick mentioned that in the 1890s, Albert’s wife, Rena, was operating a “rooming house” in Pewee Valley – an unlikely state of affairs if Albert was in control of his father’s tobacco empire:

Mrs. Dick recalled that she first met Annie Fellows Johnston as a child in the middle 1890s. She and her mother, the late Mrs. John Hoadley Cochran, stayed at a rooming house owned by Mrs. Johnston’s aunt [Burge] while the Cochrans were looking for a house in which to live in Pewee Valley.

Local accounts allege that Albert Burge was a heavy drinker and gambler who frequented the river boat casinos operating on the Ohio River at the turn of the century. Like many second generation sons, he purportedly squandered his inheritance. The experiences the Johnston family had while living under the Burges’ roof may have inspired Annie Fellows Johnston’s story of Molly and Dot illustrating the evils of drink in Chapter VI of “The Little Colonel’s Holidays,” published in 1901:

…Molly says that when she was little her father was a railroad conductor, and she and her mother and grandmother and baby sister lived in a little house at the edge of town….But Molly says one summer they moved away from the house by the railroad track and took a smaller one in town, where there wasn’t any garden and trees, and where there wasn’t even any grass, except a narrow strip in the front yard. Her father had lost his place as a conductor, and was out of work for a long time. By and by they sold their piano and the carpets and the nicest chairs. Then they moved again. This time it was to a cottage without even a strip of grass. The front door opened out on the pavement and there was no place for them to play except on the streets. Their father never brought anything home to them any more, and never played with them. They couldn’t understand what made him so cross, or what made their mother cry so much, until one day she heard some of their neighbours talking.

“She and Dot were waiting in the corner grocery for a loaf of bread, and she heard one woman say to another, in a low tone, ‘Those are Jim Conner’s children, poor little kids. My man says he used to be one of the best conductors on the road, but he lost his job when he took to getting drunk every Saturday night. He’s going down-hill now, fast as a man can go. Heaven only knows what’ll become of his family if he doesn’t put on the brakes soon.’

“… they moved again the next week. That time they had only two rooms up-stairs over a barber shop, and Molly’s mother died that summer. Then her father drank harder than ever, and never brought any money home, and by fall they had sold nearly everything that was left, and moved into one room in an old tenement-house, up two flights of stairs.

“Their grandmother had to go away every morning to look for work. She was too old to wash, or she might have had plenty to do. Sometimes she got odd jobs of cleaning, and sometimes she made buttonholes for a pants factory. It took nearly all the money she could make to pay the rent of that room, and often and often, Molly said, there were days when they had nothing but scraps of stale bread to eat. Sometimes there wasn’t even that, and she and Dot would be so cold and hungry that they would huddle together in a corner and cry. She said it made her feel so awful to hear poor little Dot sobbing for something to eat, that she would have gone out on the streets and begged, but their grandmother always locked them up when she went away.”

“What for?” interrupted Lloyd, who was listening with breathless attention.

“She was afraid that their father would come home drunk and find them alone. He didin’t live kith them any more, but several times, before she began locking them up, he staggered in, and frightened them dreadfully. Their ragged clothes and their half-starved looks seemed to make him furious. It hurt his conscience, I suppose, and that made him want to hurt somebody. Molly says he beat them sometimes till the neighbours interfered. More than once he shut them up in a dark closet, trying to make them tell where their grandmother kept her money. They couldn’t tell him, for she didn’t have any money, but he kept them shut up in the dark, hours at a time.

“One night he came in crosser than they had ever seen him, and threw things around dreadfully. He struck his old mother in the face, beat Molly, and threw a stick of wood at little Dot. It just missed putting out her right eye, and made such a deep cut over it that they had to send for a doctor to sew it up. He said she would carry the scar all her life, and he could not see how the blow had missed killing her.

“It nearly broke the old grandmother’s heart. She sat up all night, and Molly says she remembers that time like a dreadful dream. Half the time the old woman was rocking Dot in her arms, crying over her, and half the time she was walking the floor.

“Molly says that now, when she shuts her eyes at night, she can hear her saying, over and over, ‘Oh, my Jimmy! My Jimmy! To think that my only child should come to this! Oh, my Jimmy! The baby boy that was my sunshine, how can it be that you’ve become the sorrow of my life!’ Then she’d walk up and down the room as if she were crazy, calling out, ‘But it’s the drink that did it ! It’s the drink, and a curse be on everything that helps to bring it into the world.’

“Molly says that she looked so terrible, with her white hair streaming over her shoulders, and her eyes staring, that she hid her face in the bedclothes. But she couldn’t shut out the words. She shouted them so loud that the family in the next room couldn’t sleep, and knocked on the wall for her to stop. But she only went on walking and wringing her hands and calling, ‘A curse on all who buy and all who brew! A curse on every distiller! On every saloon-keeper ! On every man who has so much as a finger in this business of death! May all the shame and the sin and the sorrow they have sown in other homes be reaped a hundredfold in their own!’

“I suppose it made such a strong impression on Molly, hearing her grandmother take on so terribly, that she remembered every word, and will as long as she lives. She said the rain poured that night till it leaked down on the bed, and she and Dot had to snuggle up together at the foot, to keep dry. Her grandmother walked the floor till daylight. The neighbours complained of her, and said that her troubles had unsettled her mind, and that she would have to be sent some place to be taken care of. All she could talk about was the drink that had ruined her Jimmy, and the awful things she prayed would happen to anybody who had anything to do with making or selling whiskey.

“She couldn’t work any longer, and they were almost starving. One day she was taken to the almshouse, and the family in the next room took care of Molly and Dot until arrangements could be made to send them to an orphan asylum. It was hard to get them into one, you know, because their father was living…

After Annie returned from her European tour, the family lived for awhile with the Burges, where she wrote “The Gate of the Giant Scissors,” but in 1898, they moved to The Gables nearby, possibly in the wake of Rena Burge’s death that year. Surprisingly strong sales of “The Little Colonel” also gave Annie the financial means to rent a home. In September 1899, tragedy once again struck the little family, when Mary’s younger sister, Rena, “was taken very ill on the sixth with appendicitis. She died on the twelfth after an operation. Her death made us all the more anxious about John’s health,” Annie wrote in her autobiography.

John’s battle with tuberculosis was destined to keep the family separated for several more years. While Mary remained much of the time in Pewee Valley, Annie traveled with John in search of fresh air and sunlight, the only treatment available at that time for consumption. This excerpt from her autobiography details their travels:

A visit from Cousin Olin, who was located in New York, resulted in John’s going to Walton, New York, for a year, where he had a position which kept him out of doors, driving around the country. Just before Christmas I joined him in Walton and stayed with him till the following autumn. Then we went back to Kentucky again and the specialist who examined him said he must go immediately to Arizona.

So once more I packed my trunk and started West with him. We went to Lee’s ranch near Phoenix where we lived in tents all winter. The ranch was devoted to the care of invalid boarders. John was so much better that he could go hunting. I rented a little shack on the edge of the desert, just across the alfalfa field from the rows of tents, and fitted it up for my workshop. There I went every morning to write. I wrote the “Little Colonel at Boarding School” that winter.

In May it was so hot that we had to make a change, so we went first to California, then to Comfort, Texas, and out to another ranch for invalid boarders…In the fall Mary came out to take my place and I went to Evansville for the winter.

John and Annie ended their wanderings in Boerne, Texas where Annie bought a home she called Penacres, “…because Mrs. Johnston had earned the money to buy it with her pen,” Carrie Hoge Mead stated in her memoirs. Mary visited sporadically, according to a letter written September 23, 1908 by Annie to her friend Lilly:

Mamie went back to Kentucky in May to escape the heat. She is as much of an invalid now as John — although not from the same cause. She stayed with Hallie till July, then went to Providence, R. I. to spend three weeks with Mrs. Bliss. — (General Bliss’s widow, who has her winter home in Boerne and is one of the most charming old ladies I ever knew). Then she went back to Pewee.

Aside from health issues — which obviously couldn’t have been terribly serious, given that Mary lived to the ripe old age of 93, while her stepmother lost her 11-year fight against submaxillary (salivary) gland cancer at age 68 — were there other reasons Miss Mamie chose to stay in Pewee Valley, rather than traveling with her stepmother and brother?

Certainly, spending the winter in a tent at Lee’s Ranch would not have offered the creature comforts Miss Mamie enjoyed at Delacoosha. Such “tent communities” were common during the TB epidemic, according to the Southwestern Wonderland web site sponsored by the University of Arizona:

…At the turn of the century it was believed that the right climate, good food and rest could cure many illnesses including, tuberculosis, upper respiratory diseases and arthritis. At that time tuberculosis was known as the ‘White Plague’ and was one of the most common and most life threatening diseases. Early experiments in its treatment included convalescent care and sabbaticals to the Southwest because of the benefit of its arid climate…

Sanatoriums in those days offered a full range of accommodations. Some believed that tent camping in the higher elevations offered the best possible cure, with no other treatment except open air and sunlight. Others…offered full medical supervision and experimental treatments with heliotherapy (solar radiation) and diet…

And though Annie and John lived in a real home in Boerne, Texas, the weather there was significantly warmer than in Pewee Valley – advantageous in the winter, but sweltering during the summer months before the invention of air conditioning.

Month Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec

Boerne, Texas High Temperatures in °F 60 64.7 72 77.9 83.1 88.6 91.9 92.6 88.1 79.7 69.2 61.6

Louisville, Ky. High Temperatures in °F 41 46.6 56.8 66.8 75.4 83.3 87 85.8 79.4 68.4 55.9 45.4

In addition, Mamie was a teenager – nearly 16 – when her father remarried. It’s possible she resented returning to Evansville to live the sedate life of a minister’s daughter after her years in Pewee Valley, where Annie Fellows Johnston, herself, observed, it seemed as if “the whole world was on holiday.” Reminiscences of Mamie’s cousin, Hallie Burge Jacob, included in a September 11, 1943 “Courier-Journal” article by Hamilton Howard, enumerated some of the pleasant distractions life in the Valley afforded young women, in addition to picnics, barn dances and teas:

Life was different in Pewee those days… They would drive around to parties and entertainments all the time. We used to have house parties. Five or six men and girls came out on Saturday and stayed over Sunday. Buggy rides were a big event, but Momma didn’t allow me to go on buggy rides– just in carriages. I drove ten miles to a party in a horse break one time– you wouldn’t remember them. They were little narrow carriages with no back. My feet swung back and forth the whole way.”

Quite a contrast to life with an invalid “lunger” – even if it was her little brother! And though she undoubtedly loved him, she may also have harbored some resentment toward him and his illness for dashing her dreams of studying art, much as Mrs. Ware’s pneumonia put an end to Joyce’s studies in the “Little Colonel” stories:

From Chapter I of “The Little Colonel in Arizona:”

…”Oh, everything has come to an end now. Joyce says you can never go back when you’ve burned your bridges behind you. It was certainly burning our bridges when we sold the little brown house, for of course we could never go back with strangers living in it. It was almost like a funeral when we started to the train, and looked back for the last time. I cried, because there was the Christmas-tree standing on the porch, with the strings of popcorn and cranberries on it. We put it out for the birds, you know, when we were done with it. When I saw how lonesome it looked, standing out in the snow, and remembered that it was the last Christmas-tree we’d ever have there, and that we didn’t have a home any more, why I guess anybody would have cried.”

“Why did you sell the little home if you loved it so?” asked the girl. It was not from any desire to pry into a stranger’s affairs that she asked, but merely to keep the child talking.

“Oh, mamma was so ill. She had pneumonia, and there are so many blizzards in Kansas, you know, that the doctor said she’d never get rid of her cough if she stayed in Plainsville, and that maybe if we didn’t go to a warm place she wouldn’t live till spring. So Mr. Link bought the house the very next day, so that we could have enough money to go. He’s a lawyer. It used to be Link and Ware on the office door before papa died. He’s always been good to us because he was papa’s partner, and he gave Jack a perfectly grand gun when he found we were coming out among the Indians.

“Then the neighbours came in and helped us pack, and we left in a hurry. To-morrow we’ll be to the place where we are going, and we’ll begin to live in tents on New Year’s Day. You’d never think this was the last day of the old year, would you, it’s so warm. I ‘spose we’ll be mixed up all the time now about the calendar, coming to such a different climate.”

There was a pause while another marshmallow disappeared, then she prattled on again. “It’s to Lee’s Ranch we are going, out in Arizona. It’s a sort of boarding camp for sick people. Mrs. Lee keeps it. She’s our minister’s sister, and he wrote to her, and she’s going to take us cheaper than she does most people, because there’s so many of us… …

“How old is this Joyce?” asked the tall young fellow whom his sister called Phil. “She sounds interesting, don’t you think, Elsie?” he said, leaning over to help himself to a handful of candy.

Elsie nodded with a smile, and Mary hastened to give the desired information.

“Oh, she’s fifteen, going on sixteen, and she is interesting. She can paint the loveliest pictures you ever saw. She was going to be an artist until all this happened, and she had to leave school. Nobody but me knows how bad it made her feel to do that. I found her crying in the stable-loft when I went up to say good-bye to the black kitten, and she made me cross my heart and body I’d never tell, so mamma thinks that she doesn’t mind it at all.

Did Mamie miss her stepmother and brother during their long separations? Annie Fellows Johnston certainly thought so, as evidenced by this portrayal of Joyce’s homesickness and longing for her family in Chapter X of “Mary Ware in Texas:”

…as she sat looking into the fire, the unbroken quiet of the big room gave her an overwhelming sense of loneliness that was like an ache.

“I’d give anything to walk in and see what they’re all doing at home right now,” she thought, as she stared into the red embers, “but I can’t even picture them as they really are, because they are no longer living in any place that I ever called home.”

The thought of their being off in a strange little Texas town that she had never seen made her feel far more forlorn and apart than she would have felt could she have imagined them with any of the familiar backgrounds she had once shared with them. They seemed as far away and out of reach as they had been that winter in France, when she used to climb up in Monsieur Gréville’s pear tree and cry for sheer homesickness. That was years ago, and before the Gate of the Giant Scissors had opened to give her a playmate, but she recalled, as if it were but yesterday, the performance that often took place in the pear tree.

She began by repeating that couplet from Snowbound, —

“The dear home faces, whereupon

The fitful firelight paled and shone.”

It was like a charm, for it always brought a blur of tears through which she could see, as in a magic mirror, each home face as she had seen it oftenest in the little brown house in Plainsville. There was her mother, so patient and gentle and tired, bending over the sewing which never came to an end; and Jack, charging home from school like a young whirlwind to do his chores and get out to play. She could see Mary, with her dear earnest little freckled face and beribboned pigtails, always so eager to help, even when she was so small that she had to stand on a soap-box to reach the dish-pan. Such a capable, motherly little atom she was then, looking after the wants of Holland and the baby untiringly.

Despite the ache in her throat, a smile crossed Joyce’s face now and then, as she went on calling up other scenes. They had had hard work at the Wigwam, and had felt the pinch of poverty, but she had never known a family who found more to laugh over and enjoy when they looked back over their hard times. But now-the change was more than she could bear to think of. Jack a hopeless cripple, Mary tied down to the uncongenial work that she had to take up as a breadwinner, when she ought to be free to enjoy the best part of her girlhood as other girls were doing. Tears came into Joyce’s eyes as she brooded over the pictures she had conjured up. Then she rose, and trailing into her bedroom, came back with a lapful of letters; all that the family had written her since leaving Lone Rock four months ago. Dropping on the hearth-rug, she arranged them in little piles beside her, according to their dates, and beginning at the first, proceeded to read them through in order. They did bring the family nearer, as she had expected them to do, but the later ones brought such a weight of foreboding with their second reading, that presently she buried her face in the cushions of the chair against which she was leaning, and began to cry as she had not cried for nearly a year. Not since the first news of Jack’s accident, had she given way to such a storm of tears.

An illustration by Mary G. Johnston from “Ole Mammy’s Torment”

probably of the condemned Episcopal Church where she and Kate Matthews

would try on choir vestments

Mary Johnston’s Friendship with Kate Matthews

Miss Mamie also had many friends in Pewee Valley, including her Cousin Hallie and photographer Kate Matthews. Her association with Kate appears to have sprung from their mutual interest in art. As Annie Fellows Johnston wrote in “The Little Colonel at Boarding School,” Katie Marks – for whom Kate Matthews served as prototype — only allowed those with “artist souls” admittance to her photography studio in Clovercroft’s tower — and Mary Johnston was certainly among that elite.

The pair were a common sight in Pewee Valley’s fields and gardens — Miss Kate with her camera and Miss Mamie with her paints. Mamie was also one of Kate’s favorite models. Included in the Kate Matthews Collection at the University of Louisville’s Ekstrom Library are many photos of Miss Mamie posing as herself as well as various characters, such as Tennyson’s Elaine, a winged angel and a nun. Kate’s pictures of Mary have an ethereal quality not seen in some of her other compositions.

The two women also got into their share of mischief, as Kate recounted in a November 29, 1942 “Courier-Journal” story called “These Pictures Will Take You Back” by Bunch Brady: “Many times Kate and Mamie Johnston used to climb through a window in the condemned Episcopal Church building and dress up in the choir’s vestments.”

Examples of Mamie Johnston’s work: Above, “Summer Landscape”

oil on board, from the collection of Warren and Julie Payne

Below left, Floydsburg Cemetery in Crestwood and right, still life featuring lilies and oranges,

both from the Oldham County Historical Society’s collection.

To view more of her art, visit A Portfolio of Mary G. Johnston’s Works

Floydsburg Cemetery Landscape and Still Life in oil

Mary Johnston’s Career as an Artist

Like her stepmother, Mary Gardener Johnston’s career as an artist began as a matter of economic necessity. Cary Hoge Mead’s autobiography, “Sunshine and Shadows,” relates how Miss Mamie helped support the family early in Annie’s career as a writer:

…Annie Fellows had married Mr. Johnston, who was a widower with three children — Mamie, aged 15, Rena, aged 10, and John, aged five, who adored Mrs. Johnston and was as close as an own son. In fact, they all were, for Mrs. Johnston had the key which unlocked all hearts, especially children and young people. The children’s mother had died when John was quite little, and they welcomed this God-given mother with their whole hearts. After only two years of happiness, Mr. Johnston was taken ill, and after three years of invalidism, during which the family’s financial resources were used up, he died. This left Mrs. Johnston with three rather delicate dependents and no money. However, Mamie was a gifted artist and helped out by selling some of her paintings while Mrs. Johnston was becoming established as an author.

Chapters XI and XII of “The Little Colonel in Arizona” may offer some insights into Miss Mamie’s earliest paying commissions as an artist. In the story, Joyce Ware receives her first “order” for 30 invitations to a bridal musicale from a former neighbor in Plainsville. Though the incident is fictional, with the many specifics provided, it sounds as if it might have been based on a real commission Mary received:

From Chapter XI

Mary stole a glance at the new boarder. The long, slender fingers, smoothing his closely clipped, pointed beard, hid the half-smile that lurked around his mouth. He was leaning back in his camp-chair, apparently so little interested in his surroundings, that Mary felt that his presence need not be taken into account any more than the bamboo-arbour’s.

“Well,” she said, as if announcing something of national importance, “Joyce has an order.”

“An order,” repeated Phil, “what under the canopy is that? Is it catching?”

“Don’t pay any attention to him, Mary,” Mr. Ellestad hastened to say, seeing a little distressed pucker between her eyes. “Phil is a trifle slow to understand, but he wants to hear just as much as we do.”

“Well, it’s an order to paint some cards,” explained Mary, speaking very slowly and distinctly in her effort to make the matter clear to him. “You know the Links, back in Plainsville, Mrs. Lee. You’ve heard me talk about Grace Link ever so many times. Her cousin Cecelia is to be married soon, and her bridesmaids are all to be girls that she studied music with at the Boston Conservatory. So her Aunt Sue, that’s Mrs. Link, is going to give her a bridal musicale. It’s to be the finest entertainment that ever was in Plainsville, and they want Joyce to decorate the souvenir programmes. Once she painted some place cards for a Valentine dinner that Mrs. Link gave. She did that for nothing, but Mrs. Link has sent her ten dollars in advance for making only thirty programmes. That’s thirty cents apiece.

“They’re to have Cupids and garlands of roses and strings of hearts on ’em, no two alike, and bars of music from the wedding-marches and bridal chorus. Joyce is the happiest thing! She’s nearly wild over it, she’s so pleased. She’s going to buy a hive of bees with the money…”

From Chapter XII:

IT was nearly two o’clock next day when the thirtieth programme was finished and placed in the last row of dainty cards, laid out for the family’s farewell inspection. While Lloyd cut the squares of tissue-paper which were to lie between them, Joyce brought the box in which they were to be packed and the white ribbons to tie them.

Jack, having saddled Washington, was blacking his shoes and making other preparations for his ride to town. A special trip had to be made, in order to get the package to the Phoenix post-office in time.

“They might wait until morning, I suppose,” said Joyce, as she began placing them carefully in piles of ten. “But it is best to allow all the time possible for delays. Then the programmes have to be written on them after they get to Plainsville. Oh, I hope Mrs. Link will like them!”

“I don’t see how she can help it!” exclaimed Lloyd. “They’re lovely, and I think you’d be so proud of them you wouldn’t know what to do.”

“I am pleased with them,” admitted Joyce, stopping to take one last peep at the pretty rose-garlanded Cupids ringing the bride-bells, which Phil had suggested. It was the best design in the lot, she thought….

Mamie also helped illustrate several of her stepmother’s early books, including the original “Little Colonel” story published in 1895 and “Ole Mammy’s Torment,” published in 1897. Years later, she illustrated two cut-out paper doll books based on the “Little Colonel” series: “The Little Colonel’s Doll Book” and “The Mary Ware Doll Book,” both published in 1914.

Above, illustrations from ”The Little Colonel Doll Book” and below,

cover of the Mary Ware Doll Book

Her works included oil paintings of landscapes and flowers, as well as pen and ink sketches. After her brother John’s death in 1910 and the family’s subsequent move to The Beeches, she had a studio on the home’s third floor. Annie Fellows Johnston’s description of Joyce’s New York art studio in Chapter X of “Mary Ware in Texas” bears some resemblance to her comfortable studio at The Beeches:

IT was a wild, blustery day in March, two months after Mary’s interrupted visit at the ranch. Joyce Ware, sitting before the glowing wood fire in the studio, high up on the top floor of a New York apartment house, had never known such a lonesome Sunday. The winds that rattled the casements and sent alternate dashes of rain and snow against the panes had kept her house-bound all day.

Usually she was glad to have one of these shut-in days, after a busy week, when she could sit and do nothing with a clear conscience. Every moan of the wind in the chimney and every glimpse of the snow-whitened roofs below her windows, emphasized the luxurious comfort of the big room. She had had a hard week, trying to crowd into it some special orders for Easter cards. A year ago she would not have added them to her regular work, but now she was afraid to turn anything away which might help to swell the size of the check she must send home every month. If the days were not long enough to do the tasks she set for herself at a comfortable pace, she simply worked harder — feverishly, if need be, to finish them.

…to make the day as different as possible from the six others in the week, in which she sat at her easel from morning till night in a long-sleeved gingham apron, she went into her room and put on a dress of her own designing, soft and trailing and of a warm wine-red. Pushing a great sleepy-hollow chair close enough to the hearth for the tips of her slippers to rest on the shining brass fender-rail, she settled herself among the cushions with a book which she had long been trying to find time to read.

…she paused for a moment to look around her. There were several things which gave her keen pleasure every time her attention was called to them, which she felt ought to be enough of themselves to dispel her vague depression: the odor of growing mignonette, the sunny yellow of the pot of daffodils on the black teakwood table, the gleam of firelight on the brasses, and the warm shadows it cast on the trailing folds of her wine-red dress.

That lighting was exactly what she wanted for some drapery folds which she would be putting on a magazine cover next week. She studied the effect, thinking lazily that if it were not her one day of rest, she would get out palate and brushes, and make a sketch of what she wanted to keep, while it was before her.

One question yet to be answered is whether Mary, like her fictional counterpart Joyce, had an older artist take an interest in her and offer her free instruction. In the stories, it is Mr. Armand, whom Joyce meets as a boarder/patient at Lee’s Ranch in Chapter XIII of “The Little Colonel in Arizona:”

[Left: Illustrator Etheldred Barry’s conception of Mr. Armond, shown here with Joyce from “The Little Colonel in Arizona”]

[Left: Illustrator Etheldred Barry’s conception of Mr. Armond, shown here with Joyce from “The Little Colonel in Arizona”]

“Mr. Armond is an artist, mother, a really great one, who has had pictures hung in the Salon and the Academy. Mr. Ellestad walked part of the way home with me, and told me about him. He studied for years in Paris, and lived in the Latin Quarter, and had a studio there, just like Cousin Kate’s friend, Mr. Harvey. And that’s the man Mr. Armond looks like,” she added, triumphantly. “I’ve been trying to think ever since I first met him, who I had seen before with a short Vandyke beard like his, and long, alive-looking fingers, that seem to have brains of their own.”

“And that’s what makes you so glad,” laughed Lloyd, ” to think you’ve discovered the resemblance? Do get to the point. I’m wild to know.”

“Well, he liked my work, thought it showed originality and promise, and, if mamma is willing, he wants to give me lessons. Think of that, Lloyd Sherman, — lessons from an artist, a really great artist like that! Why, it would mean more for me than years of class instruction in the Art League, or anywhere else. He seemed pleased when I told him that I wanted to do illustrating, because he said that that was something practical, and work that would find a ready market. He told me so many interesting things about famous illustrators that he has known, that I have come away all on fire to begin. My fingers fairly, tingle. Oh, mamma!” she cried, two great happy tears welling up into her eyes. “Isn’t it splendid? The story of Shapur is true! For me the desert holds a greater opportunity than kings’ houses could offer!”

“But the price, my dear little girl — “

“And that’s the best of it,” interrupted Joyce. “He asked to be allowed to do it for nothing. Time hangs so heavily on his hands that he said it would be a charity to give him something to do, and Mr. Ellestad told me afterward, as we walked home, that I ought to let him, because it’s the first thing that he has taken any interest in for months; that with something to occupy his mind and make him contented, he would get better much faster.

“When I tried to thank him, and told him that he had showed me a better way to the City of my Desire than the one I had planned for myself, he said, with the brightest kind of a smile, ‘I expect to get far more out of this arrangement than you, my little girl. You are the alchemist whose courage and hope shall help me distil some drop of Contentment out of this dreary existence.’

“He is going to drive up here to-morrow, to ask you about it, and to see the work I have already done. I’m glad now that I saved all those charcoal sketches of block hands and ears and things. And I’m going to get out all those still life studies I did with Miss Brown, and pin them up on the wall, so he’ll know just how far I’ve gone, and where to start in with me.”

“Get them out now,” said Lloyd. “You never did show them to me.”

There was some very creditable work hidden away in the old portfolio, and, while they talked and looked and arranged the studies on the wall, time slipped by unnoticed.

Although Pewee Valley was home for a time to two respected artists, Carolus Brenner and Herbert Ross, neither fits as the model for Mr. Armond.

Landscape artist Carolus Brenner (1838-1888), known for his paintings of beech trees, was originally from Germany, where he also attended art school. Though he did exhibit at the National Academy of Design, he did not exhibit or study in Paris.

On first glance, Herbert Ross (1895-1989) seems to a better match, since he studied in Paris and had his works exhibited at the Grand Salon; however, he did not go to Paris until 1922 — 18 years after the publication of “The Little Colonel in Arizona.” He was 23 years Mary’s junior, too young to offer her instruction.

It could be, then, that there may have in fact been an artist that Annie Fellows Johnston met at Lee’s Ranch that she had had in mind for this character of Mr. Armond. Or he may have been a fictional soul meant only to impart a another of Annie’s many lessons on life.

Some of Mary Johnston’s paintings and sketches from private collections can be viewed in a Portfolio of Mary Gardner Johnston’s Works

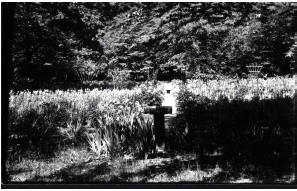

Mary Johnston in her Garden at the Beeches in Pewee Valley

Photo by Kate Matthews

The Lady of the Lilies, c. 1910

Oil on canvas, 25-5/8 x 36-5/8 inches

Collection, The Speed Art Museum, Louisville

Patty Prather Thum (1853-1926) after a photo by Kate Matthews

Mary Johnston’s Garden

“Miss Mamie had a beautiful flower garden, as did Miss May Dulaney, and we girls used to think how wonderful it would be to be married in one of those gardens — we couldn’t decide which. Of course, that was silly, as we would not have dreamed of being married anywhere except in the beautiful little church,” Cary Hoge Mead wrote in her autobiography.

Some of the flowers Mary cultivated in The Beeches’ backyard included rubrum lilies (also known as Oriental Lilies or Lilium Speciosum Rubrum) and daffodils. Privileged were those who were allowed to cut a bouquet, says Steve Conn, who grew up at The Gables next door and was among the fortunate few.

Miss Mamie’s garden at The Beeches was photographed frequently by her friend, Kate Matthews.

Kate Matthews Collection, Photographic Archives, Ekstrom Library, University of Louisville

Mary Johnston and Life at The Beeches

Mary G. Johnston lived at The Beeches for 55 years, from 1911 until her death in 1966. For 35 of those years, after her stepmother’s death in 1931, she lived alone. The following are memories of Mary Johnston by those who met her or had the pleasure of calling her friend. If you have a memory of your own to contribute, please email us at e-mail@littlecolonel.com. We’d love to add them here.

From Delinda S. Buie, a “Little Colonel” fan since she was a child and currently Curator, Rare Books for the Ekstrom Library at the University of Louisville

I met her at The Beeches when I was maybe 8. She showed me the beech trees in front of the house and told me that people were always wanting to cut them down and use them for whiskey barrels. She told me to remember to tell anyone who tried to cut them down after she died that she would come back to haunt them.

From Pewee Valley Town Historian Virginia Herdt Chaudoin, as related in “History By Food: Recipes and Stories about the Food and Families of Oldham County, Kentucky,” published by the Oldham County Historical Society, 2006, pg. 56:

One afternoon in the 1940s, the ladies of Pewee Valley Presbyterian Church were invited to “The Beeches” for tea by Mary G. Johnston (we called her Miss Mamie). Miss Mamie was the stepdaughter of Annie Fellows Johnston, the author of The Little Colonel Books. The Beeches had been Miss Annie’s home until her death in 1931.

Miss Mamie asked me to serve. As I sat at the table and poured the tea, the maid came to me and asked, “You called?”

“No,” I said.

This happened two more times. Each time, I assured the maid that I hadn’t summoned her. Finally Miss Mamie leaned over to me and said, “Ginny dear, you are touching the bell button on the floor under the dining room table with your foot.” Never was I aware that such a thing existed…

Mary Johnston’s Death

“Miss Mamie” died on July 16, 1966 at Pewee Valley Sanitarium & Hospital. Her obituary, which appeared the following day in the “Courier-Journal” is transcribed below:

‘Little Colonel’ Illustrator Dies at 93

Miss Mary Gardner Johnston, 93, artist and illustrator of the “Little Colonel” books, died at 6 a.m. yesterday at the Pewee Valley Hospital. She had been there since September with a broken hip.

Miss Johnston had lived in The Beeches, in Pewee Valley, where her stepmother, Annie Fellows Johnston, wrote the “Little Colonel” books which Miss Johnston illustrated. The series was written for young girls.

Miss Johnston also exhibited some of her paintings at the J.B. Speed Art Museum.

A native of Evansville, Ind., she moved to Pewee Valley when she was 10. She was a member of the Pewee Valley Presbyterian Church, the Pewee Valley Woman’s Club, the Oldham County Historical Society and the Kentucky Historical Society.

The funeral will be at 10 a.m. Monday at Pewee Valley Presbyterian Church. Burial will be at 3 p.m. Monday at Oak Hill Cemetery, Evansville. The body is at M.A. Stoess & Son Funeral Home in Crestwood.

She is buried in Oak Hill Cemetery in Evansville, Indiana, with her father, mother, stepmother, brother and sister. Her last will and testament is on file at the Oldham County Courthouse. In it, she makes monetary bequests specifically to Walker J. Hardin, son of the Walker Hardin who served as Annie Fellows Johnston’s model for the Old Colonel’s body servant in the “Little Colonel” stories, and to Mrs. Frank Pancoast, whose late husband once headed Frost National Bank in San Antonio, Texas. Frank Pancoast appears to have served as her stepmother’s – and later Miss Mamie’s – financial advisor. In Annie Fellows Johnston’s will, Frank V. Pancoast was mentioned as follows:

I have in charge of Frank V. Pancoast, Frost National Bank of San Antonio, Texas, Real Estate lien notes and mortgages amounting to Thirty six thousand Dollars, and of the said investment (be it more or less at my death) I bequeath to my said daughter Thirty Four Thousand Dollars.

In a codicil to her will dated April 12, 1931, Annie Fellows Johnston also bequeathed “Five Hundred Dollars worth of Liberty Bonds” to Frank Pancoast.

From Miss Mamie’s will, it’s evident she dreamed The Beeches would become a shrine to her late stepmother. Unfortunately, that never happened. After her death, it was sold and remains a privately-owned residence today.

LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT OF MARY G. JOHNSTON

I, MARY G. JOHNSTON, a resident of Pewee Valley, Oldham County, Kentucky, do make, publish and declare this to be my last will and testament, revoking all wills and codicils heretofore made by me.

ITEM I.

I give to WALKER J. HARDIN, if he survives me, the sum of Three Hundred Dollars ($300) in cash.

ITEM II.

I give to DELANO (Mrs. Frank) PANCOAST of San Pedro Manor, 616 West Russell Avenue, San Antonio, Texas, if she survives me, the sum of Five Hundred Dollars ($500) in cash.

ITEM III.

I give to the PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH of Pewee Valley, Kentucky, the sum of One Thousand Dollars ($1,000) in cash.

ITEM IV.

I give the cottage and lot on which it stands, adjoining my residence in Pewee Valley, to MR. AND MRS. FRANKLIN B. CONN of Pewee Valley, Kentucky, in fee simple. I give to STEPHEN CONN, if he survives me, the sum of Five Hundred Dollars ($500.00) and to MRS. FRANK B. CONN, if she survives me, the sum of Five Hundred Dollars ($500.00).

ITEM V.

I give to HELEN O’DELL of 626 South Harlan Avenue, Evansville, Indiana, my mother’s portrait; provided, however, that if within six (6) months of my death my home is made into a shrine, this bequest shall be void. Any transportation charges for shipping the portrait shall be borne by HELEN O’DELL.

ITEM VI.

I give to MARY MUNGER of 2755 Buena Vista, Southwest, Portland, Oregon, if she survives me, the portrait of me (head); provided, however, that if my home is made into a shrine within six (6) months of my death, this bequest shall be void. Any transportation charges for shipping the portrait shall be borne by MARY MUNGER.

ITEM VII.

I devise my home, ‘THE BEECHES,” in Pewee Valley, Kentucky, to such as shall survive me of JOY BACON WITTWER of Route 4, Box 197, Niles, Michigan, and DR. HILARY E. BACON of 5506 Kemper Road, Baltimore, Maryland; if both survive me they shall take equally in fee simple.

ITEM VIII.

All the rest and residue of my estate, I give to such of the following as shall survive me: HELEN O’DELL; LURA E. HEILMAN, JR. of Congress Hotel, 1024 Southwest Tenth Avenue, Portland Oregon; MARY MUNGER; DR. HILARY E. BACON; DR. ANNE E. HEILMAN of 1314 Glenview Avenue, Glenview, Illinois; and MISS MARY JANE EAVES of 1227 West Broadway, Mayville, Kentucky, in equal shares. Any taxes against specific bequests of cash or personal property made in this will shall be paid out of the residue of my estate and not charged to the beneficiary thereof.

ITEM IX.

I request that JOY BACON WITTWER take over the handling of the “LITTLE COLONEL” copyrights (L/C. Page & Company, 19 Union Square, West, New York 3, New York) that I have handled for my family for many years, and my mother’s diary.

ITEM X.

I nominate and appoint KENNEDY HELM, JR. of Louisville, Kentucky to be the Executor of this my last will and testament. If he is unable or unwilling to qualify and serve, I appoint the BANK OF OLDHAM COUNTY Executor. My Executor shall have full power and authority to pay all debts, taxes and expenses of administration; to sell and dispose of any all of my estate, real and personal, or both, except the real estate referred to herein, and that also if it be necessary to pay debts, for such prices and upon such terms (including credit) and in such manner as my said Executor in his uncontrolled discretion may deem best, and to execute and deliver to the purchaser or purchasers all necessary or proper deeps and other instruments of conveyance in transfer. I authorize and empower my Executor, in the settlement of my estate, to compromise, compound, adjust and settle any and all debts and liabilities due to and from my estate, for such sums and upon such terms and in such manner as my said Executor in his uncontrolled discretion shall deem best. All the foregoing powers may be exercised without first obtaining the approval of any court.

I request that my Executor be allowed to qualify without surety on his bond.

ITEM XI.

I desire that I be buried in OAK HILL CEMETERY, Evansville, Indiana, and that a small granite marker be placed at my grave; and I wish Two Hundred Dollars ($200) to go to the upkeep of my lot in OAK HILL CEMETERY, in Evansville, Indiana.

IN TESTIMONY WHEREOF, I have hereunto subscribed my name to this last will and testament, consisting of this and three (3) preceding typewritten pages, and for the purpose of identification I have initialed each such page, all in the presence of the personas witnessing it at my request this 21 day of April, 1965, at Pewee Valley, Kentucky.

Witnessing her last will and testament were Lucille L. Apple and Fred J. Kilgus, Jr.

Mary Gardner Johnston lived at the Beeches for most of her life, not only as a step-daughter, but in many ways a best friend to Annie Fellows Johnston. She did some writing of her own, and was an accomplished artist in oils. She died at The Beeches on July 16, 1966, at the age of 93.

Mary Johnston walking in downtown Louisville, date unknown, from the private collection of Suzanne Schimpeler

Mary Johnston walking in downtown Louisville, date unknown, from the private collection of Suzanne Schimpeler

Mary Johnston on the Front Porch of The Beeches 1951

Mary Johnston on the Front Porch of The Beeches 1951

Mary at home at the Beeches,

Mary at home at the Beeches,

late in her life (ca. 1960s)

(Samuel Culbertson Mansion Collection)

page by Donna Russell