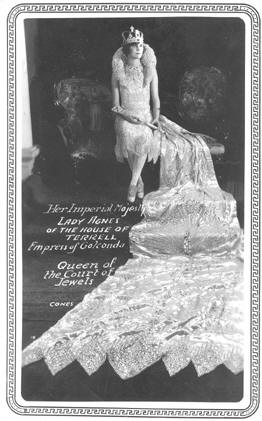

San Jacinto Day in San Antonio, Texas

Photo showing an early Order of the Alamo ceremony

with the Fiesta queen, king and royal court,

courtesy of the Fiesta Commission of San Antonio

Chapter 14 of Mary Ware in Texas is almost entirely devoted to a description of San Jacinto Day celebrations in San Antonio :

IT was the twentieth of April when Phil returned to Bauer, and for the second time his visit was cut disappointingly short. The reason was that he had promised Major Melville the night he dined with him, to be back in San Antonio in time for the Carnival. The Major wanted to take him to a Mexican restaurant for a typical Mexican supper the night of the twenty-first. On the twenty-second there would be an entertainment for the Queen of the Carnival at her Court of the Roses; something too unique and beautiful for him to miss, they all said. Then, on the twenty-third, San Jacinto Day, which all loyal Texans keep as a state holiday, the annual Battle of Flowers would take place in the plaza in front of the Alamo, which they call their “Cradle of Liberty.”

The Flower Battle was an old institution, the Major explained. But this was only the second year for the Queen’s Court, and it was something so surpassingly beautiful that he thought it ought to become a regular feature of every carnival.

Roberta, who was also at the dinner, added her persuasions.

“You’ll think you’re back in the time ‘when knighthood was in flower,’” she insisted. “I wish every Easterner accustomed to poking fun at our state could see it. Nobody knows what I suffered at school from having people talk as if all Texans are ‘long horns.’”

“Roberta was one of the duchesses last year,” explained Lieutenant Boglin. “You should have seen her sweep up to the throne when they announced, ‘Her Grace, the Lady Roberta of the House of Mayrell!’ She certainly looked the real article, and was a far cry from a long-horn then.”

“Don’t emphasize the then so pointedly, Bogey,” ordered Roberta.

…The stage of Beethoven Hall was turned into a bower of roses on this eve of San Jacinto Day, and a great audience, assembling early, awaited the coming of the Queen of the Carnival and her royal court. In the patent of nobility given by her gracious majesty to her attendants, was the command

“We bid you to join with all of our loyal subjects in the Mirth and Merriment of this Festival of Flowers, which doth commemorate the glorious freedom of this, our Texas, won by the deathless heroism of the defenders of the Alamo, and the Victory of San Jacinto.”

This call for Mirth and Merriment struck the keynote of the carnival, and everyone in the great assembly seemed to be responding with the proper festival spirit.

Back in the crowded house in a seat next the aisle and almost at the entrance door, sat Mary Ware, completely entranced by all that was going on about her. Lieutenant Boglin was beside her, and in the chairs directly behind them were Gay and Billy Mayrell. Roberta and Phil were in front of them. They had come early to secure these chairs, and the men had given the girls the end seats in order that they might have unobstructed view of both aisle and stage. They all turned so that conversation was general until the house was nearly filled, then Roberta said something which drew Phil’s attention wholly to herself, and he turned his back on the others, beginning to talk exclusively to her.

Gay, who appeared to know at least every fourth person who came down the aisle, sat, like most of the audience, with her head turned expectantly towards the door, and kept up a running comment to Mary on the acquaintances who passed her with nods of recognition or brief words of greeting. The thrum of the orchestra, the sight of so many smiling faces, although they were strange to her, and the blended colors of fashionable evening gowns would have furnished Mary ample entertainment after her dull winter in the country; but it was doubly entertaining with Gay to point out distinguished people and give her bits of information, supplemented by Billy and Bogey about this one from the Post and that one from the town.

She wished that Phil could hear too. She wanted him to know what prominent personages he was in the midst of. Once when some world-known celebrity was escorted up the aisle she leaned over and called his attention to the procession. He looked up with a smile to follow her glance, and made a joking response, but returned so quickly to the fascinating Roberta, that Mary felt that his interest in everything else just then was merely perfunctory.

…A hush fell on the great audience, and the curtain rose on a tableau of surpassing loveliness. The stage seemed to be one mass of American Beauty roses. The walls were festooned and garlanded with them. They covered the high throne in the centre and bordered the steps leading up to it. They hung in long streamers on either side from ceiling to floor. Grouped against this glowing background, stood the noble dukes, the lords-in-waiting and their esquires. The gay-colored satins and brocades of their old-time court costumes, the gleam of jewelled sword-hilts, the shine of powdered perukes, transported one from prosaic times and lands to the old days of chivalry and romance.

The jester shook his bells, the trumpeters in their plumed helmets raised their long, shining trumpets, and sounded the notes that heralded the first approach. Then the Lord Chamberlain stepped forth in a brave array of pink satin, carrying the gold stick that was his insignia of office.

“That’s my friend,” whispered Gay, “the man who originated this affair. I tell him I think he must be one of the Knights of the Round Table re-incarnated, or else the wizard Merlin come to life again, to bring such a beautiful old court scene into being in the way he has done.”

She stopped whispering to hear the impressive announcement he was making, in a voice that rang through the hall: “Her Grace, Lady Elizabeth, of the House of Lancaster!”

[Left: An example of the long, glistening trains worn by the Fiesta queen’s court, courtesy of the Fiesta Commission of San Antonio]

[Left: An example of the long, glistening trains worn by the Fiesta queen’s court, courtesy of the Fiesta Commission of San Antonio]

Immediately every eye turned from the stage to look at the rose-trimmed entrance door. The orchestra struck into an inspiring march and the stately beauty, first to arrive at the Court of Roses, began her triumphal entry up the long aisle. She passed so near to Mary that the tulle bow on the directoire stick she carried almost touched her cheek with its long floating ends, light as gossamer web. And Mary, clasping her hands together in an ecstasy of admiration, noted every detail of the beautiful costume in its slow passing.

“It’s like the Princess Olga’s,” she thought, recalling the old fairy-tale of the enchanted necklace. “Whiter than the whiteness of the fairest lily, fine, like the finest lace that the frost-elves weave, and softer than the softest ermine of the snow.”

The long court train that swept behind her was all aglisten, as if embroidered with dewdrops and pearls. Mary watched her, scarcely breathing till she had ascended the steps to the stage. Then her appointed duke came forward to meet her and led her to the steps of the throne.

The music stopped. Again the heralds sounded their trumpets and the Lord Chamberlain announced the next duchess.

“You see,” explained Gay, hastily, as all necks craned toward the door again,” each girl is duchess of some rose or other, like Killarney or Malmaison or Marechal Niel.”

One after another they passed by to take their places beside the throne, all in such exquisitely beautiful costumes that Mary thought that each one must be indelibly photographed on her memory. But when they had passed, all she could remember of so many was a spangled procession of court trains, covered with cascades of crystal and silver and pearls and strung jewels.

Each time a new duchess swept slowly and majestically by, Mary turned a quick glance toward Phil to see if he were properly impressed; but when the Queen was announced, she had no eyes for anything but the regal figure proceeding slowly up the aisle, amid the admiring applause which almost drowned the music of the march.

It was at this juncture that Phil glanced back at Mary. Her face so plainly showed the admiration which filled her that he continued to watch her with an amused smile, saying to Roberta in an undertone:

“Look at Mary’s rapt expression! She’s always adored queens and such things, and now she feels that she’s up against the real article.”

“I don’t wonder,” answered Roberta, herself so interested that she turned her back on Phil until the royal party had passed by. Two little pages in costumes of white and gold, with plumed hats and spangled capes, bore the royal train, and Roberta tried to upset the dignity of one of them, who was a little friend of hers, by whispering, “Hello, Gerald, where did you get that feather?”

In Mary’s estimation it was not the diamond crown that marked the Queen as especially regal, nor the jewelled sceptre nor the white satin gown, heavily embroidered in gold roses and gleaming with brilliants; it was the fact that the long train borne by the little pages was of cloth-of-gold. ..

The presentation scene followed. In the name of The Order of the Alamo, the Queen was given a magnificent necklace, with a jewelled pendant. After that the visiting duchesses were received, representing many towns of Texas, from El Paso to the gulf. They came with their maids of honor, and when they had been met by their lords-in-waiting and their esquires, the entertainment for the Queen began.

Grecian maidens bearing garlands of roses danced before her. The second group was of seven little barefoot girls, carrying golden lyres, and forming a rainbow background for another small maid who gave a cymbal dance. The Grecian dances were followed by a gavotte of the time of Louis XIII, in which all the dukes and duchesses took part.

“They danced the minuet last year,” commented Gay. “This is the end of the performance, but we’ll wait to watch them go out, on their way to the Queen’s ball. I went to that too, last year. These are good seats; we catch them coming and going.”

The audience remaining seated until all the members of the Court had passed out two by two, had ample time for comment and observation. Bogey, who, seeing Mary’s absorbing interest in the scene, had considerately left her undisturbed most of the time, now leaned over and began to talk. As Gay had once said, “When it comes to giving a girl a good time, Bogey is quite the nicest officer in the bunch,” and Phil, overhearing scraps of their conversation, concluded that Mary was finding her escort as entertaining as the pageant. A backward glance now and then showed that she was not watching the recessional as closely as she was listening to him.

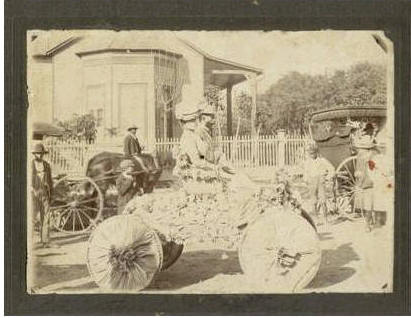

The Battle of Flowers Parade in 1902, above, and 1903, below. 1901

was the first year motorized vehicles joined in the parade.

As they all started out of the hall together, moving slowly along with the crowd, barely an inch at a time, they talked over arrangements for the next day. Lieutenant Boglin could not be counted in. He had to ride in the procession with the rest of the troops from the Post who were to take part in the parade. Billy Mayrell had another engagement, so Phil proposed to take all three of the girls under his wing. It was too late to secure seats in the plaza from which to watch the flower battle.

Battle of Flowers Parade courtesy of the Fiesta Commission of San Antonio

The Major had been able to get only two. So Phil said the Major and his wife should occupy those. He would come around for the girls in an automobile and they could watch the parade seated in that.

There was a blockade near the door, but as soon as they could get through it, they all walked up the street to a building in which the Major had secured the use of a second-story window, from which they could watch the parade of the Queen and her court on their way to the ball. The time spent in waiting was well worth while, when it finally appeared. The horses of the chariots were led by Nubian servants, and each chariot represented a rose, wherein sat the duchess who had made it her choice.

A flower bedecked carriage courtesy of the Battle of the Flowers Association

The Queen’s chariot was surmounted by a mammoth American Beauty rose, and as she smiled out from the midst of its petals, Mary had one more entrancing view of the royal robes. This time they were lit up by the red gleam of torches, for eight torch-bearers, four on a side, accompanied each chariot, and added their light to the brilliant illuminations of the streets.

“You must see the river,” said Billy Mayrell, after the procession had passed by. “Nobody can describe it, with the lights strung across it from shore to shore all down its winding course. It makes you think of Venice.”

He led them to a place where they could look across a bend and see one of the bridges. It was strung so thickly with red lights which outlined every part, that it seemed to be made of glowing rubies, and its reflection in the water made another shining ruby bridge below, wavering on the dark current.

Mary leaned over the rail watching the shimmering lights, and feeling dreamily that this City of the Alamo was an enchanted city; that the buildings looming up on every side were not for the purpose of barter and trade. They were thrown up simply as backgrounds for the dazzling illuminations which outlined them against the night sky. The horns of the revellers answering each other down every street, the music of distant bands, the laughter of the jostling throngs, all deepened the illusion.

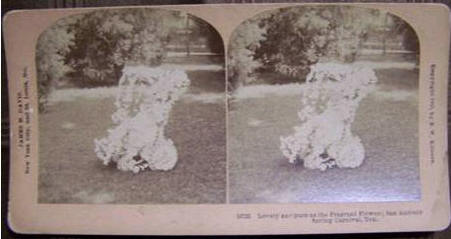

A 1905 stereo card by B.W. Kilburn showing a baby in a stroller bedecked with flowers

and captioned, “Lovely and pure as the Fragrant Flowers, San Antonia Spring Carnival, Texas.”

For over a century, the residents of San Antonio have been honoring the fallen heroes of The Alamo and the victory at the Battle of San Jacinto that won Texas her independence with celebrations during the week of April 21. The event now known as Fiesta was started in 1891 by local women who organized the first Battle of Flowers Parade, featuring horse-drawn carriages, bicycles and floats decorated with fresh flowers.

Over time, other events have been added. Today, the celebration lasts 10 days and includes over 100 events, from pageants and sports tournaments to art shows, fireworks and balls. In early years, residents referred to the week of April 21st as “Carnival,” “Spring Carnival” and “Fiesta San Jacinto.” In 1959, when the Fiesta San Antonio Commission was created to oversee the celebration, the name was changed to Fiesta San Antonio, its official name now for half a century.

The Battle of Flowers Parade is the oldest and original event, but other Fiesta traditions have also reached the centennial mark. Among them are the activities at Ft. Sam Houston and the Fiesta queen. “In 1896, the United States decided to recognize this important historical event by staging a 21-gun salute at Fort Sam Houston. That tradition continues today on Fiesta Sunday,” says Anne Keever Cannon, public relations manager for the Fiesta San Antonio Commission. That same year the first Fiesta queen was crowned.

It was four more years before a Fiesta queen had a court. According to the Battle of Flowers Association, Lola Kokernot’s court in 1900 included a princess, duchess and other attendants as well as royal robes. Parade royalty, however, remained “hit or miss” until 1909, when John B. Carrington, secretary of the San Antonio Chamber of Commerce, founded the Order of the Alamo, an all-male group responsible for choosing the queen and her court. According to Cannon, “Selection as queen is one of the highest honors San Antonio society can bestow. Most queens come from the inner circle of old aristocracy. Heritage, not money, is the principal criterion. The queen’s court includes a princess, 12 in-town duchesses and 12 from out of town. This royalty is featured in the major Fiesta parades.”

The elegant gowns worn by the queen and her court are the stuff of legend – yard upon yard of expensive materials encrusted with beads, crystals and rhinestones hand-sewn to form intricate designs. The trains of the queen and princess can measure as long as 18 feet, the duchesses, 15. According to the Fiesta San Antonio Commission, the gowns cost from $10,000 to $35,000 apiece and are paid for by the families.

Today, Fiesta has six queens: the Order of the Alamo Queen and her court, who represent the Fiesta at all the official events; Miss Fiesta San Antonio; the Charro Queen, who represents the Charro association, which sponsors a “charreada” or Mexican rodeo; the Queen of Soul; a Teenage Queen; and Miss San Antonio, who goes on to compete in the Miss Texas pageant and, if she wins the state title, the Miss America pageant.

Author Annie Fellows Johnston appears to have attended the San Jacinto Day celebration in 1910. The novel specifically states that it “was only the second year for the Queen’s Court” and mentions The Order of the Alamo in the description of the presentation scene below:

In the name of The Order of the Alamo, the Queen was given a magnificent necklace, with a jewelled pendant. After that the visiting duchesses were received, representing many towns of Texas, from El Paso to the gulf. They came with their maids of honor, and when they had been met by their lords-in-waiting and their esquires, the entertainment for the Queen began.

From this passage, it also appears she knew John B. Carrington:

“That’s my friend,” whispered Gay, “the man who originated this affair. I tell him I think he must be one of the Knights of the Round Table re-incarnated, or else the wizard Merlin come to life again, to bring such a beautiful old court scene into being in the way he has done.”

Annie herself would have been among the “prominent personages” and “world-known” celebrities who attended the event. By April 1910, she was a famous children’s author and had received requests to have her works translated into French, German, Spanish, Italian, Japanese and even Braille.

We know the Johnstons didn’t attend the celebration in 1908 from a letter Annie wrote on April 19, while she was hard at work on Mary Ware: The Little Colonel’s Chum, the predecessor to Mary Ware in Texas in the Little Colonel series:

“The Carnival begins tomorrow in San Antonio with its Battle of Flowers and parades, and we are

thankful we are up in the hills “far from the madding crowd.”

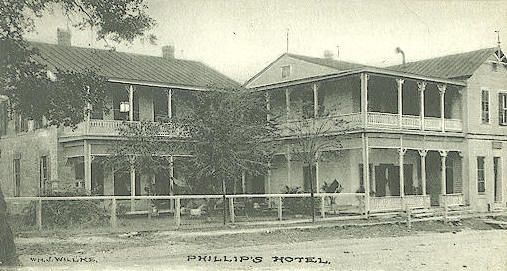

Hardworking Annie, however, may not have managed to sidestep quite all the mirth and merriment. Though 30 miles away from San Antonio, the Queen and her court reputedly visited Boerne for several years at the end of Fiesta, where they received the “royal treatment” at Phillip House/Phillip Manor, according to the Boerne Area Historical Preservation Society:

In 1872 a hall was added and used as a church for religious revival meetings, also a shooting gallery was installed and different kinds of festivities were had here. Sometimes the hall was used as a kind of city Auditorium for diverse public meetings. In 1883 the frame hall was rebuilt of stone and a large stage added where local and traveling theatrical troupes performed. At the close of the first Fiesta Celebration in San Antonio, and for several years thereafter, the reigning Queen with her personal attendants were entertained with dinner parties at the Phillip Manor House by members of the association.

For more about Phillips House/Phillips Manor/Phillip’s Hotel

and the role it played in Mary Ware in Texas, visit The Little Colonel’s Boerne page.

Thanks to Anne Cheever Cannon, Public Relations Manager of the Fiesta San Antonio Commission for providing the information on the Fiesta origins and traditions and to the Boerne Area Historical Preservation Society for the information about Phillips House.

Page by Donna Andrews Russell

Copyright 2009