Annie McCown Craig

(February 11, 1834 – October 20, 1914)

Real Life Model for Grandmother McIntyre/MacIntyre in Annie Fellows Johnston’s “Little Colonel” Stories

Mistress of Edgewood

Matriarch of the Craig family, which eventually served as models for 12 characters in the “Little Colonel” stories

Annie Fellows Johnston described Mrs. MacIntyre’s

silvery hair in “The Little Colonel’s Christmas Vacation

Kate Matthews Collection, Photographic Archives, Ekstrom Library, University of Louisville

Annie Fellows Johnston first mentions Mrs. MacIntrye – grandmother of Keith and Malcolm MacIntyre and Virigina Dudley; mother of Aunt Allison; and mistress of Edgewood – in the Chapter I of “Two Little Knights of Kentucky,” when Keith and Malcolm meet the tramp, Jonesy and the bear at the Lloydsboro Valley Railroad Station:

“Is your home near here, my little gen’leman?” he asked, in a friendly tone.

“No, we live in the city,” answered Malcolm, “but my grandmother’s place, where we are staying, is not far from here.” He was stroking the bear with one hand as he spoke, and hunting in his pocket with the other, hoping to find some stray peanuts to give it.

“Then maybe you know of some place where we could stay tonight. Even a shed to crawl into would keep us from freezing. It’s an awful cold night not to have a roof over your head, or a crust to gnaw on, or a spark of fire to keep life in your body.”

“Maybe they’d let you stay in the waiting-room,” suggested Malcolm. “It is always good and warm in here. I’ll ask the station-master. He’s a friend of mine.”

….Grandmother is afraid for anybody to sleep in the barn, on account of fire,” he said, after a moment’s thought, “ and I’m sure she wouldn’t let you come into the house without you’d had a bath and some clean clothes. Grandmother is dreadfully particular,” he added, hastily, not wanting to be impolite even to a tramp. “Seems to me Keith and I have to spend half our time washing our hands and putting on clean collars.”

Throughout the story, Mrs. MacIntyre is portrayed as a strict, but loving grandmother, endeavoring to both civilize and protect her young charges from harm, such as in the following passage from Chapter VII:

The children promised at least a dozen things. They would keep away from the barn, the live stock, the railroad, the ponds, and the cisterns. They would not ride their wheels, climb trees, nor go off the MacIntyre premises, and they would keep a sharp lookout for snakes and poison ivy, in case they went into the woods for wild flowers.

Malcolm and Keith, of course, find ways to get around their grandmother’s admonitions:

“Oh, wait just a minute!” begged Malcolm, throwing down his book. “Let’s all play Indian this afternoon. We’ll rig up, too, and build a wigwam down by the spring rock, and make a fire, — grandmother didn’t say we couldn’t make a fire; that’s about the only thing she forgot to tell us not to do.”

Annie Fellows Johnston also portrays Mrs. MacIntyre as a woman of stern moral rectitude who worries about exposing her grandchildren to life’s baser elements when she argues against allowing then to visit Jonesy while he convalesces from his burns at Professor Heinrich’s cottage in Chapter IV:

And to think that that terrible man was harboured on my place!” exclaimed Mrs. MacIntyre when she heard of it. “And you boys were down there in the cabin with him for hours! Sat beside him and talked with him! What will your mother say? I feel as if you had been exposed to the smallpox, and I cannot be too thankful now that the boy who was with him was not brought here. He isn’t a fit companion for you. Not that the poor little unfortunate is to blame. He cannot help being a child of the slums, and he must be put in an orphan asylum or a reform school at once. It is probably the only thing that can save him from growing up to be a criminal like the man who brought him here. I shall see what can be done about it, as soon as possible.”

…”What a blessing that there are such places as orphan asylums for children of that class,” said Mrs. MacIntyre, after one of her visits to him. “I must make arrangements for him to be put into one as soon as he is able to be moved.”

“I think he will be very loath to leave the old professor,” answered Miss Allison. “He has been so good to the child, amusing him by the hour with his microscopes and collections of insects, telling him those delightful old German folk-lore tales, and putting him to sleep every night to the music of his violin. What a child-lover he is, and what a delightful old man in every way! I am glad we have discovered him.”

“Yes,” said Mrs. MacIntyre; “and when this little tramp is sent away, I want the children to go there often. I asked him if he could not teach them this spring, at least make a beginning with them in natural history, and he appeared much pleased. He is as poor as a church mouse, and would be very glad of the money.”

“That reminds me,” said Miss Allison, “he asked me if the boys could not come down to see Jonesy this afternoon, and bring the bear. He thought it would give the little fellow so much pleasure, and might help him to forget his suffering.”

Mrs. MacIntyre hesitated. “I do not believe their mother would like it,” she answered. “Sydney is careful enough about their associates, but Elise is doubly particular. You can imagine how much badness this child must know when you remember how he has been reared. He told me that his name is Jones Carter, and that he cannot remember ever having a father or a mother. I questioned him very closely this morning. He comes from the worst of the Chicago slums. He slept in the cellar of one of its poorest tenement houses, and lived in the gutters. He has a brother only a little older, who is a bootblack. On days when shines were plentiful they had something to eat, otherwise they starved or begged.”

…”His speech is something shocking; nothing but the slang of the streets, and so ungrammatical that I could scarcely understand him at times. No, I am very sure that neither Sydney nor Elise would want the boys to be with him.”

Later on in the chapter, however, Miss Allison plays on her mother’s strong sense of morality and persuades her to not only let the children visit Jonesy but to help raise money to create a real home for him in the Valley, rather than sending him to an orphanage:

When Miss Allison kept her promise she did not go to her mother with the children’s story of Jonesy, to move her to pity. She told her simply what they wanted, and then said, “Mother, you know I have begun to teach the children the ‘Vision of Sir Launfal.’ Virginia has learned every word of it, and the boys will soon know all but the preludes. There will never be a better chance than this for them to learn the lesson:

“Not what we give, but what we share,

For the gift without the giver is bare.’

“This would be a real sharing of themselves, all their time and best energies, for they will have to work hard to get up such an entertainment as this. It isn’t for Jonesy’s sake I ask it, but for the children’s own good.”

The old lady looked thoughtfully into the fire a moment, and then said, “Maybe you are right, Allison. I do want to keep them unspotted from a knowledge of the world’s evils, but I do not want to make them selfish. If this little beggar at the gate can teach them where to find the Holy Grail, through unselfish service to him, I do not want to stand in the way. Bless their little hearts, they may play Sir Launfal if they want to, and may they have as beautiful a vision as his!”

Annie McCown Craig, Annie Fellows Johnston’s real-life inspiration for Grandmother MacIntyre’s character, was born February 11, 1834 in Harrodsburg, Kentucky. She was the second oldest of four children born to the Rev. Burr Hamilton and Mary (Thompson) McCown. According to Samuel W. Thomas, author of “The Village of Anchorage,” published in 2004 by the Anchorage Civic Club, Annie’s father:

…B.H. McCown was born in 1806 and was given the name of Burr Hamilton, honoring the famous duelists, Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton. He received his education, particularly in Latin and Greek, at St. Joseph’s College in his native Bardstown. After becoming a minister in the Methodist Episcopal Church, he moved to Louisville, where the “young divine became fast friends” with George Prentice, editor of “The Louisville Journal.” He then taught at Augusta College and Transylvania University…

At the time of the 1850 census, Rev. B. H. McCown was employed as a “preacher O.S.P.” in Christian County, Kentucky and was living with his wife, Mary, and all four children: Elizabeth M., 18; Anna, 16; Alexander, 14; and Letitia, 11.

Shortly after the 1850 census, the family relocated to the Louisville area, where in 1856 her father founded a military school for young men known as Forest Academy on 31 acres he purchased from Edward Dorsey Hobbs near Hobbs’ Station (later Anchorage), just two whistle stops west of Lloydsboro/Pewee Valley. An advertisement for Forest Academy that ran in the September 6, 1858 “Louisville Daily Courier” quoted the fledgling school’s fees as $20 for tuition and $60 for room and board per 21-week session. By the 1860 census, Rev. McCown and his wife Mary was living at O’Bannon, Kentucky (between Pewee Valley and Anchorage) with their youngest child, Letitia, who was then 18.

The Forest Academy building as it looked in 1900 when it was a summer boarding house, above,

from the Isabelle Lyman Anderson Collection, Anchorage Civic Club Archives.

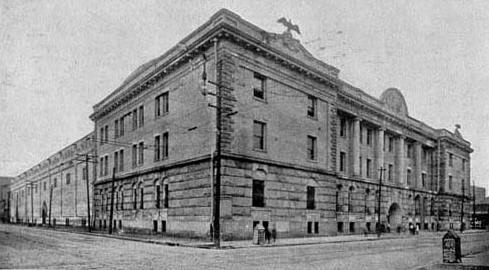

On February 9, 1854, Annie McCown married Aleck/Alexander Craig in Oldham County, Kentucky. According to the Louisville City Directory of 1859, he had a hat and cap business at 419 and 425 Main Street and lived on Walnut Street between 6th and 7th, later the site of the Jefferson County Armory.

1906 post card of the Jefferson County Armory, built in 1905 on the site

where Aleck and Annie Craig’s Louisville home once stood.

The Armory is now Louisville Gardens.

While living in Louisville, Annie gave birth to five of the couple’s seven children:

- Mary Craig, wife of Henry Ware Lawton (March 31,1855 – January 5, 1934)

- Aleck Craig (November 21, 1856 – December 25, 1923)

- Alice Craig, wife of Austin L. Peay (April 19, 1860-December 13, 1881)

- Fanny Craig (February 9, 1859 – March 14, 1933)

- Burr Harrison McCown Craig (Nov 15, 1863 – November 1, 1929)

In 1864, the Craigs purchased Edgewood at auction and moved their brood to Lloydsboro/Pewee Valley, where two more children were born:

- Louise Craig, wife of Samuel Culbertson (October 26, 1865 – September 10, 1938)

- Merton Craig (1869-?)

The Craigs’ decision to move to Pewee Valley may have been influenced by the City of Louisville’s unhealthy reputation. That Annie’s father and mother were living in O’Bannon – the next train station west of the Valley — may have also been a factor. The fact that Pewee Valley offered regular train service to Louisville also made it possible for Aleck to make the daily commute to his millinery and fur business, Hayes & Craig hatters & furriers, later Craig, Truman & Co., on Main Street.

A tree planting at the Pewee Valley Presbyterian Church, ca 1903,

around the time of The Little Colonel at Boarding-School

L to R: Mrs. Lawton, Miss Laura Woodruff, Miss Florence Matthews, Miss Fanny Craig,

Rev. Mr. Creighton, Mrs. Annie Craig and Miss Frances Lawton

or in Little Colonel terms:

Mrs. Walton, Miss Laura Woodruff, Miss Florence Matthews, Miss (Aunt) Allison,

Rev. Mr. Creighton, Grandmother McIntyre and Allison Walton

Kate Matthews Collection, Photographic Archives, Ekstrom Library, University of Louisville

On November 17, 1866, Aleck and Annie Craig attended an organizational meeting for what would later become the Pewee Valley Presbyterian Church at Sycamore Chapel Methodist Church in Rollington. Annie was the Presbyterian church’s oldest living member when she died in 1914.

Annie experienced her share of trials and tribulations during her 80 years. Her fifth child, Burr Harrison McCown, known to family and friends as “Harry,” was born simple-minded and required supervision all of his life. She was pregnant with her last child, Merton J., when her husband died at age 53 on October 7, 1868. Her husband never got to see her youngest son and Annie was left to raise their seven children alone.

In 1872, Annie’s mother, Mary Thompson McCown, died and was buried in Cave Hill Cemetery, Section 0, Lot 297, Grave 4. A year later, according to “The Village of Anchorage,” her father offered to give the Forest Academy property rent-free for five years to the newly chartered Central University. The deal, which would have netted him $25,000 at the end of the five years, fell through when Central University (now Eastern Kentucky University) chose Richmond, Kentucky for their site in 1874. Rev. McCown revived Forest Academy for a few years, but eventually sold the property in 1878 for $6,000 and then opened Pine Hill Academy nearby. He also remarried, choosing “Pattie Duke, the daughter of Scott County horseman James K. Duke” as his bride. He had another daughter by her, Sallie McCown Green. We can only speculate about Annie’s relationship with her new stepmother and the stepsister who was younger than her own children.

The same year (1873) that her father was attempting to sell Forest Academy to Central University, Annie Craig was working to establish an educational institution for young ladies in Pewee Valley. According to “History & Families Oldham County Kentucky: The First Century 1824-1924,” published by the Oldham County Historical Society in 1996, page 248:

…The college was to be a private, non-denominational school. Among those lending support to E. F. Gallagher in this undertaking were P.B. Muir, J. M. Armstrong, H. M. Woodruff, A. W. Kaye, Henry S. Smith, W. B. Gray, and Mrs. Annie Craig…The Kentucky College for Young Ladies was incorporated in 1876 with the objective of educating young ladies in literature, science and the arts…

Her daughter, Fanny Craig, graduated from the Kentucky College for Young Ladies in 1877 and later taught there.

The former Pine Hill Academy at it looks today, located at 12402 Lucas Lane in Anchorage

From “The Village of Anchorage,” by Samuel W. Thompson, published by the Anchorage Civic Club, 2004

Annie’s father died on August 29, 1881 at his Pine Hill home and was buried in Lot 5 of Hobbs Memorial Cemetery in Anchorage.

Above, Hobbs Chapel and burial ground in Anchorage, c. 1936, where the Rev. B. H. McCown is buried,

and a recent photo of all that remains of the Methodist-Episcopal chapel after it was destroyed by a fire in 1954

1936 photo from the Kentucky Digital Library, Herald-Post photographs collection

The small burying ground is located down a long, grassy path behind the chapel

and is enclosed by a stone fence and iron gate. Rev. B. H. McCown’s tombstone is in Lot 5

Just a few months later, Annie lost her third oldest child, Alice Craig Peay, and assumed responsibility for raising her infant granddaughter, Alice, named after her mother. At the time of Alice’s illness, Annie’s oldest daughter, Mary (Mamie), had recently become engaged to be married to U.S. Army Captain (later General) Henry Ware Lawton. Sensing the end was near, Alice begged her sister to marry quickly so she could attend the wedding. Mamie quickly sent a telegraph to Henry and he obtained leave and left for Louisville by special train. This sad wedding took place on December 12, 1881 at Alice’s death bed. Alice died the next day. Alice’s death thus actually meant the loss of two daughters to Annie Craig, since Mamie Craig Lawton followed her husband wherever he was called to serve his country, from the Indian Wars until his death in the Philippines in late 1899.

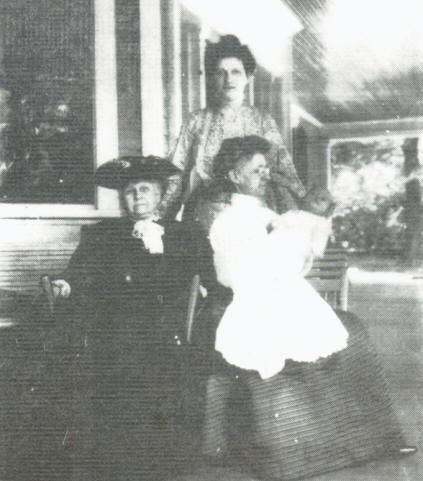

Mrs Annie Craig (seated left) “Grandmother McIntyre” approx. 1908 to1910?

Also in the photo are Fannie Craig “Miss Allison” holding Baby Frances

and (standing) Alice Craig Peay, whose mother (Annie’s daughter and Fanny’s sister) died when she was an infant.

(This photo appears to be taken on the front porch of “The Beeches”

which was home to Annie Craig’s widowed daughter, Mamie Lawton “Mrs. Walton”)

Five years later, Edgewood was again the setting for a wedding. This one, however, was a much happier occasion. Annie’s youngest daughter Louise married millionaire Samuel Culbertson on April 6, 1886. A transcript of their simple wedding invitation is shown below:

******************

Mrs. Annie Craig

requests your presence

at the Marriage of her daughter

Louise

to

Samuel Alexander Culbertson

Tuesday Evening, April Sixth

at six o’clock

Edgewood

Pewee Valley

1886

******************

A write-up of their high society wedding appeared in April 7, 1886 edition of The New Albany Ledger:

The marriage of Mr. Samuel A. Culbertson, Cashier of the First National Bank of this city, and Miss Louise Craig, took place Tuesday evening at 6 o’clock at the residence of the bride’s mother at Pewee Valley, Ky, Rev. Dr. Reynard, of the Presbyterian church, officiating. The bride is a highly accomplished lady, very popular in society both at Pewee and Louisville. The wedding was very quiet, the invited guests numbering but seventy five. Mr. and Mrs. Culbertson left two hours after their marriage for New York, whence they sail Saturday for Europe. The bride wore a handsome toilet of white satin and tulle, the dress being entirely covered with the lighter material, giving the costume an exceedingly graceful appearance. Mr. Culbertson has a host of friends in New Albany who wish him bon voyage.

And in the “Redden Scrapbook:”

Craig – Culbertson

Last night, at the residence of the bride’s mother, at Pewee Valley, Miss Louise Craig, a young lady well known, popular and an ornament to society was wedded to Mr. Samuel Culbertson, son of the wealthy W. S. Culbertson of New Albany. Both the contracting parties stand high in social circles. The wedding was a comparatively quiet one, only about seventy-five near friends being present. Rev. Mr. Raymond, Pastor of Pewee Valley Presbyterian Church, officiated. Mr. and Mrs. Culbertson left for New York immediately, after the ceremony. The bridal tour will go to Europe – The bride’s costume was of white satin and tulle – The wedding was characterized by quiet elegance, and the bridal gifts were very costly.

A year later, Mamie Lawton’s first child Annie – and Annie Craig’s grandchild and namesake — died at Fort Huachuca, Arizona on April 26, 1887. In a poignant letter Mamie wrote to her mother less than two weeks after her daughter’s passing, she talked about her unbearable grief, how much she missed her mother’s comforting presence, and her hope that she was as good a mother to her late daughter as her own mother was to her:

… It was such a comfort, and pleased me much to have you think me a devoted Mother to my little Heartease though I know very well I deserve no credit, for she was not only the best, sweetest, baby a Mother ever had, but I had your example before me. I always wanted to be to her, what you were to us….

It was somewhere around this time that Annie Fellows Johnston, while staying at The Gables across the road from Edgewood, first met the Craig family. She soon incorporated their home and all the female members of the Craig clan into her popular “Little Colonel” stories. Beginning with the 1899 publication of “Two Little Knights of Kentucky,” 12 members of the Craig family eventually served as the models for characters in the series:

- Annie McCown Craig became “Grandmother/Mrs. MacIntrye”

- Her daughter, Fanny Craig, became “Aunt Allison”

- Her daughter, Louise Craig Culbertson became Aunt Elise McIntrye and her son-in-law, Samuel Culbertson, became Uncle Sidney McIntyre.

- Their two sons, William Stuart Culbertson and Alexander Craig Culbertson became “Malcolm and Keith McIntyre,” the Two Little Knights of Kentucky.

- Her daughter, Mary “Mamie” Craig Lawton, first appeared in the tales as Mrs. Dudley and in later books, Mrs. Walton. Her husband, Henry Ware Lawton, was also appears in the stories, first as Captain Dudley and later as General Walton.

- Their four children also served as models for characters: Manly became “Ranald Walton, ‘The Little Captain;’” Frances became “Allison Walton;” Catherine became “Kitty Walton;” and Louise became “Elise Walton.”

The familial relationships described in the “Little Colonel” tales were based on fact, with the exception of Sidney and Elise McIntyre. In the stories, Sidney was portrayed as the son of Grandmother McIntyre, but in real-life, he was her son-in-law, making Annie Craig the maternal, rather than paternal, grandmother of the Two Little Knight of Kentucky.

The same year that “Two Little Knights of Kentucky” was published, Mamie Craig Lawton’s husband, by then a General in the Spanish American War, was killed in action in the Philippines. Mamie returned to Louisville and in 1902 built The Beeches across the street from her mother.

Tragedy visited the Craig family once again in 1909, when Annie’s granddaughter, Alice Craig Gatchel, who she had helped raise since birth, died on March 8, 1909 at age 28, leaving behind her husband, Frank Gatchel, and two young children, Frances and William or “Billy.”

In 1911, her oldest daughter, Mamie, moved from the Pewee Valley home she built after her husband died to Annapolis, Maryland. Annie’s four unmarried children continued living at Edgewood: Alexander “Aleck,” Fanny, Harry and Merton.

Annie McCown Craig died October 20, 1914 and was buried in Cave Hill Cemetery. A transcript of her obituary from the October 21, 1914 “Courier-Journal,” is shown below.

MRS. ANNIE MQUOWN CRAIG DIES AT AGE OF 85 YEARS

WIDOW OF LOUISVILLE FUR AND HAT MERCHANT KNOWN THROUGHOUT SECTION

Mrs. Annie McQuown Craig, 85 years (NOTE: She was actually 80 at the time of her death and her maiden name was spelled “McCown”), one of the best-known residents of Jefferson county, died of infirmities at 9:15 o’clock yesterday morning at “Edgewood,” her home near Pewee Valley. “Grandmother Craig,” as she was known, enjoyed good health until a year ago. Her condition became serious about ten days ago. Members of the family were at the bedside when she died.

Mrs. Craig was born in Harrodsburg, Ky., and was the daughter of Prof. Alexander McQuown, who conducted a school at Forest, near Anchorage. (NOTE: the school was Forest Academy and it was actually located between Anchorage and O’Bannon, Ky.) She married Alexander Craig, a fur and hat merchant of Louisville, who died 42 years ago. (NOTE: She was actually widowed for 46 years, as her husband died in 1868.)

Her husband was the founder of the Pewee Valley Presbyterian church, and Mrs. Craig was the oldest living member. Her home was the scene of many social functions and was the setting for the “Little Colonel” stories by Annie Fellows Johnston, which enjoyed wide popularity.

She is survived by three daughters: Mrs. Louise Culbertson of Louisville; Mrs. Mamie Lawton, widow of Gen. Henry W. Lawton, who was killed in the Philippines; and Miss Fannie Craig; three sons, Alexander, Harry and Merton Craig; six grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

The grandchildren are A. Craig Culbertson and William C. Culbertson, Mrs. Leroy Gayheart, Mrs. Oliver Bagby,Miss Catherine Lawton and Manley Lawton.

Funeral services will be conducted at the Pewee Valley Presbyterian Church at 10:00 o’clock tomorrow morning. Burial will be at Cave Hill Cemetery.

Her last will and testament is on file at the Oldham County Courthouse:

I, Annie Craig, being in sound mind and body do make this my last will and testament.

1st, I hereby devise and bequeath to my daughter Fanny Craig, my place in Pewee Valley, Oldham County, Kentucky, containing about twenty-nine acres, more or less, together with all the houses and buildings thereon, and all the contents thereof, including furniture, pictures, plate, china, carpets, books, bed and table linen, and all the horses, cattle, vehicles and farming implements on said place.

2nd I devise and bequeath all the rest of my property to be equally divided between my children, and my granddaughter, Alice Pay; that is my estate is to be divided into seven equal parts, excluding the property left in the 1st clause above of my will, and Alice Peay is to have one such part.

3rd, I appoint my daughter, Fanny Craig, as executrix of this my last will, and desire that she be allowed to qualify without giving bond and that no inventory is required of her.

4th The share of my property which my son Burr Harrison McCown Craig will receive under this will I leave to my daughter Fanny Craig in trust for my said son.

In testimony whereof I have hereunto set my hand this seventh day of March, 1892.

I, Annie Craig, make this codicil to my will. If my granddaughter, Alice Peay, should die unmarried, or without issue before she arrives at the age of twenty-on years, her portion of my property under this will shall go to my children equally, and in the event of this happening, my son Harrison’s portion shall be held in trust for him by my daughter, Fanny Craig. Witness my hand this 7th day of March, 1892.

Witnessing her last will and testament were her attorney, William Christy Churchill, and her neighbor, Mary Van Horn.

page by Donna Russell, 2007

Donna is the current mistress of Edgewood